MEXICO CITY — It started with 27 rail cars full of ammunition rolling down the tracks into Mexico.

That load of 30 million bullets was soon followed by fleets of Black Hawk helicopters and thousands of Humvees: in all more than $1 billion of U.S. military equipment sold to Mexico within the past two years.

In a security relationship between Mexico and the United States often described as standoffish, foreign military sales have lately become a big exception. Admiral William E. Gortney, the commander of Northern Command, the U.S. military headquarters that deals with Mexico, testified to the U.S. Congress earlier this year that Mexico’s buying binge represented a “100-fold increase from prior years.”

What explains the shopping spree?

People in the U.S. and Mexicans familiar with the foreign military sales program said that the change in part reflects a revived security partnership between the two countries. It also shows Mexico’s aggressive push to modernize its military in the face of powerful drug cartel adversaries.

U.S. officials have hailed the sales in part because they’re so rare. Gortney, the Northcom commander, described Mexico’s decision to approach the Defense Department about buying military equipment as “unprecedented” and that it marked a “historical milestone” in relations between the two countries.

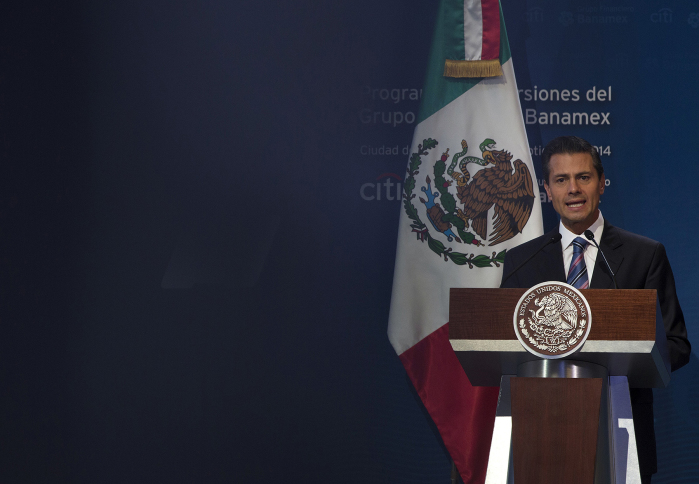

Mexico’s long been suspicious of Gringo motives (at least since it lost about half a million square miles of its territory to the U.S. in the 19th century) and has tended to not be a big U.S. military buyer, relying more on European equipment or private commercial agreements. At the start of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s term more than two years ago, his administration felt the United States had wormed its way too deeply into the drug war, and Mexico halted many security programs.

“We knew that the president came in really wanting to focus on things other than security,” said a U.S. military official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly. “He found out he really needed to pay a lot of attention to security.”

In late 2013, Mexico asked the United States if it could fill a large order of 5.56 mm ammunition, and the embassy helped deliver the trainloads of $6 million worth of bullets within 100 days, the official said.

“That case really kind of broke the ice,” he said. “They saw the responsiveness of what we could do as a partner in foreign military sales. And they liked it.”

That sale paved the way for even larger purchases: orders for more than two dozen UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters for the Air Force and Navy, and more than 2,200 Humvees. Since Peña Nieto came to office in late 2012, Mexico has purchased about $1.5 billion in equipment through the government’s military sales program, plus $2 billion more through U.S. companies, said Inigo Guevara Moyano, a Mexican defense consultant based in Washington.

“All of these buys have been to replace existing systems that averaged 30 to 40 years old and drained budgets through high maintenance costs and poor availability,” he said. He noted that defense spending also rose sharply under Peña Nieto’s predecessor, Felipe Calderón, and that it reflects the “maturing military-to-military relationship at the institutional level, regardless of who is in power.”

The buying also is a sign of the intensity of the war against the drug cartels. The Mexican military has aggressive operations ongoing in several states such as Tamaulipas, on the Texas border, and Jalisco, against the ascendant New Generation drug cartel. These operations have driven a rapid increase in defense spending over much of the past decade. Since 2006, spending has tripled, from $2.6 billion to $7.9 billion this year. Despite the growth, Mexico spends less than many other countries in the hemisphere, just .51 percent of gross domestic product, compared to a Latin American average of 1.31 percent, Guevara said.

In addition to tactical raids and statewide operations against drug cartels, the Mexican military is involved in all sorts of other missions, from vaccination programs, to reforestation, to securing voting booths in volatile parts of the country, as it did last week. The lavishly funded drug cartels it fights are sometimes better armed and equipped than the security forces. Cartel gunmen recently shot down a Mexican military helicopter with a rocket-propelled grenade.

“The Mexican armed forces, including the Army, is one of the most overtasked military forces in the world,” said Alejandro Hope, a security analyst.

Some have been critical of the U.S. sales, particularly in a climate where Mexican security forces have regularly been accused of human rights violations. Last year, 43 teachers college students disappeared in Guerrero, allegedly captured and killed by local police working with drug gangs. A few months earlier, 22 civilians were killed by the Mexican military in the town of Tlatlaya south of Mexico City. The army first described the incident as a firefight but later admitted that a number of the civilians had been executed after surrendering. Relatives of the 42 men killed last month on a Michoacán ranch have accused the authorities of torturing and executing them, claims the government denies.

Researcher John Lindsay-Poland wrote for the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) that the “massive militarization” is “bad news for the many Mexicans devastated by the abuses of police and soldiers.”

“The United States must develop other capacities besides producing guns and military equipment for finding a healthy balance of trade and addressing our own problems,” he wrote.

But others see this as necessary maintenance and modernization for an under-equipped military.

“It’s mainly a process of correcting the imbalance,” Hope said. “Having Humvees will not affect how much respect they have for human rights.”