All day long, you can hear their voices.

“¡Kölbi! ¡Claro! ¡MoviStar!”

“¡Aguacates! ¡Cinco por quinientos! ¡Aguacates!”

“¡Plátanos aquí, plátanos!”

They chant and call. They gesture and gesticulate. They rock on the balls of their feet and swing their arms at their sides. Dozens of vendors stand in the street, anxiously calling to everyone who passes, a great chorus of prices and offerings. Floods of humanity pour past them in all directions, side-stepping their blankets spread out on the ground. The sidewalk is a quilt of objects – cell phones, tennis shoes, remote controls, purses, leather wallets, pirated DVDs with faded covers, wind-up toys juddering across the pavement.

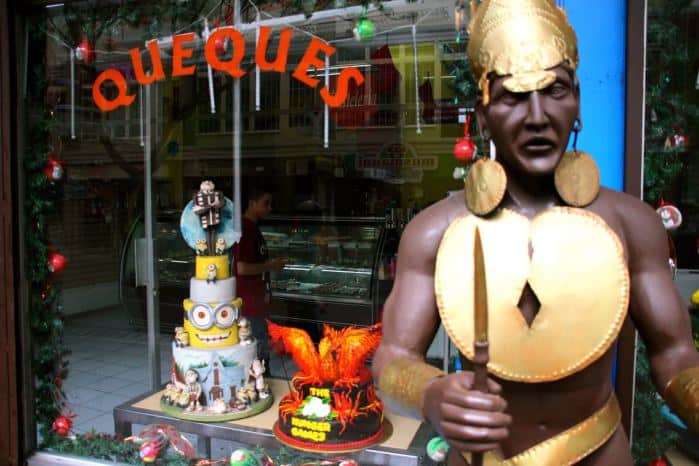

This is Avenida Central, the fluttering heart of San José, the 12-block pedestrian walkway that divides the city in half. Avenida Central is the Times Square of Costa Rica, absorbing people from all over the world. Avenida Central is a market and carnival and public art gallery and freak show rolled into one endless arcade. Waves of people roll down the brick causeway, heads bobbing like buoys in a vast human sea.

I have walked this street at least 400 times, because Avenida Central is part of my daily commute. I could drive, but it’s faster and safer to ride the bus and then walk the 1.5 km from parada to oficina. Normally I stuff headphones into my ears and wear sunglasses, even on overcast days. This is how I defend myself against the endless queue of hawkers and panhandlers. Squirrelly men spot me, ready to gush their life story and ask for spare change, but when they see my dead expression, my determined stride, they fall away. I can actually see them make the decision to retreat. No vale la pena, says their morphing expression. That Gringo’s just gonna be a dick.

But in mid-November, I removed the sunglasses and pocketed the ear buds. For the first time in months, I could hear the mariachi band playing music beneath a tree. I listened to the blend of a thousand conversations, and I forced myself to make eye-contact with passing salesmen. I spotted the leathery woman blowing bubbles, and although I normally avoid her every day, I tried to nod pleasantly. (She ignored me.) I saw the man with no limbs in his wheelchair, whose faded cardboard sign read, “NO PUEDO TRABAJAR,” and I dropped a 100-colón coin in his cup. I stepped into a clothing store and asked a saleswoman if they had sports jackets.

“For a formal event,” I asked. “Or maybe a suit?”

“No,” said the woman, shaking her head. “We don’t carry suits.”

Then she stared at me expectantly, as if to say, Is that all you wanted? Because you can totally leave now.

I didn’t have to do this. It would have been easier not to. San José has a way of punishing friendly behavior. It sometimes seems that I can’t smile warmly or hold a door for a stranger or try to make small talk with a cashier without eventually regretting the effort. But as Black Friday approached, I wanted to interact with the city. The storefronts and billboards I had always ignored now emerged, like mirages in the desert, and I wondered what lay inside. Instead of avoiding passersby like dangerously contagious lepers, I took a moment to notice them and see what they were selling.

In the weeks before Christmas, the city swells with activity. The crowds are twice as thick. A handful of hawkers becomes a corridor of hawkers. Twice as many signs plaster the windows, twice as much graffiti is sprayed on the walls, and twice as many teenagers hand out flyers and coupons – which means twice as much cardboard is trampled into the pavement. To prevent pre-Christmas mugging, packs of police officers surge the streets, and observation towers rise at intersections so they can scan the throngs for pickpockets. As usual, people still walk blindly toward me, silently demanding that I step out of their way, but the number of people doubles, as does their intensity.

As a rule, I never run into anyone I know in San José – but I do see the same revue of “characters,” and I started to realize how many regulars there were: The frightened-looking man in the black trench coat, the middle-aged guy selling gadgets in the doorway of an abandoned building, and the angry old man in a wheelchair with his fistful of lollipops, to name a few. Most of them were harmless and familiar. Others were sketchy and unpleasant, no matter how many times I saw them.

As every chepeño knows, these touts aren’t supposed to sell their stuff on the streets. Every hour or so, the salesmen and women will dive to the ground, bundle their items in a blanket, and shuffle away. The process takes only a matter of seconds, because that’s how much time they have before the police show up and break up their camp. But it’s hard to say how serious this relationship is. I’ve watched police officers walk casually past hawkers without a peep. I’ve never once seen a hawker fined or arrested. The ritual has always seemed so arbitrary, and I’ve never understood how hawkers signal each other, why they only fear certain cops, and what consequences they face for selling plastic action figures out of a cardboard box.

“You want a toothbrush?” said a skinny young man with a scruffy chin.

“No, thank you,” I said, pushing past.

He leaned toward me. “What do you want? Anything, I can get it for you.” But he said it so quickly that it came out as a jumble of English syllables. “Whatdoyouwantanythingicangetitforyou.” Then he added, “Coke? Weed? I can get it for you, man.”

I almost stopped, not because I was in the market for illicit substances, but because I wondered what his game was. Did he always start by trying to sell toothbrushes, then shift the conversation to stamp bags? Did that work for him? Or was it all a longwinded scam? Who knew? I kept walking.

•

This was my curiosity: Why would anyone shop in San José?

As I breezed through unfamiliar stores, the question intensified. Yes, the streets are packed with tiendas, but most of them are small and eccentric. Did people actually commute from Moravia or Curridabat to visit a particular shoe store on Avenida Central? Did anyone make a special trip to the kiosk full of ceramic angels, or did they buy their Virgin Mary figurines on a whim? It seemed incredible that people would make an effort to visit dirty, ominous Avenida Central for the fun of it, especially when San José’s suburbs have their own walkable business districts. Where did all these people come from? And why did they come here?

As Christmas shoppers deluged San José, vendors erected tents in the many parks and plazas, creating ad hoc bazaars for jewelry and fried rice, and I browsed their many tables in a passive search of gifts. The problem with these shops is that most of them sell junk – the kind of cheap, mass-produced tchotchkes you’d find in a U.S. dollar store. I enjoy open-air markets, because they feel urgent and intimate. But I couldn’t imagine buying a baseball cap with a marijuana leaf, or a plastic hand mirror, or a “Pura Vida” dish towel. I wondered who would eventually take home the small purse covered in teddy bears, or the dream catchers made out of woven twine.

But permanent stores sell similar knick knacks and are open year-round. I had never before stepped foot in “Zapateria Novedades Imperial” (“Imperial Novelty Shoe Store”) or “K Barato” (“How Cheap”). Some places were so odd that I was wary to even glance inside: The shop next to the Tuasa bus station sold power drills, electric guitars, fake gold rings, and a range of blenders. It was like an SAT question – which one of these items does not belong? The answer: All of them.

I assumed that most people visited San José for the experience of shopping, not because they sought anything in particular. I understood this mentality well, for I had spent most of my adolescent years window-shopping in used bookstores. From a buyer’s perspective, this made sense. People gravitate toward San José for all sorts of reasons – they have jobs downtown, or they meet friends, or they have an appointment with a doctor or attorney. As long as they’re making the trip, they might as well peruse the Lee Jeans store, which sells nothing but denim trousers. Like, why not?

But this seemed frustrating for the shopkeepers, who must welcome droves of aimless customers. Most patrons make slow circles around the store and then buy nothing. I couldn’t imagine the proprietors’ daily lives, especially around Christmas, when the pressure to sell is so feverish.

One morning, I stepped into a souvenir shop near my office. The store occupied a quiet street corner and the façade was covered in tropical murals. The store specialized in Boruca artwork. I had passed the place dozens of times but never once considered going inside. There I chatted with the clerk, a jovial woman who had lived her entire life in Tibás, a quiet suburb north of San José.

“I’ve always worked in tourism,” she told me. “My country is a beautiful country. I like to see people on vacation. But the business is seasonal.”

She said the biggest sellers were wood products from Sarchí. She gestured to shelves full of bowls and decorations.

“How many people come in during an average day?” I asked.

She screwed up her face as she considered this. “Five or six.”

“Five or six?” I blurted.

“More or less.”

“Who are they? Is there a typical customer?”

“Typical? Well, they’re all foreigners.”

“From where?”

She shrugged. “North America. Europe. All over.”

“Do you think business will pick up in December?”

She laughed morosely. “We’ll see.”

This is what confounds me – how such tiny stores can stay in operation with such few and unreliable customers. Small businesses are extremely expensive to run in Costa Rica. Between rental fees, taxes, Caja enrollment, and utility payments, it was astonishing that these stores could stay open at all. Suddenly it dawned on me why mini-super stores in the countryside often keep their lights off. Friends sometimes suggest that many of these shops are just fronts for more nefarious operations.

Later that day, as I started to leave one of the tents in Central Park, a tall young man handed me a brochure. I looked at the cover image of flowers and a smiling family, and I realized that it was an ad for a funeral home.

“We have monthly deals,” he said helpfully.

I hoped I wouldn’t have to call him anytime soon.

•

On the highways around San José, billboards now advertise jobs at Amazon.com. The Seattle-based super-corporation is opening its fourth call center in Costa Rica, and soon even more support service calls will be directed to the Central Valley. The irony is that only a tiny fraction of Amazon deliveries are made to Costa Rica.

Yet for retails stores, this is a boon: Without widespread Internet commerce, Costa Ricans still shop in brick-and-mortar stores. While shopping centers have been closing across the United States, Costa Rican malls are still overrun with customers. Indeed, Multiplaza Escazú is among the largest malls in Central America, attracting visitors from across the isthmus. Instead of scaling back its shopping complexes, Costa Rica is building its largest one yet – a 200,000 square meter leviathan in Alajuela. The designers are calling the project a “mega-mall.”

As Black Friday approached, I had mixed feelings. On the one hand, I dreaded “Viernes Negro,” the national shopping spree that Costa Rica had inherited from the United States like a debilitating virus. Black Friday seemed so silly in Costa Rica, given how attached it was to Thanksgiving, the quintessential U.S. holiday. Meanwhile, I already recoiled at the sight of “NEGRO” signs everywhere, a distinctly uncomfortable arrangement of letters for a speaker of U.S. English. Then I saw Black Friday posters that were quietly expanding its definition: “Semana Negra,” then “Mes Negro.” Were they serious? Did Black Friday really have to last an entire month?

Then again, as a journalist, I felt it was important to see a full-scale retail disaster as it unfolded. People in the United States get a sick satisfaction from watching their countrymen camp out in front of Target and trample each other in their scramble for bargains. Since my homeland had already infected Costa Rica with fast food, box stores, and beltway traffic jams, surely it was important for me to witness Black Friday firsthand. TV commercials and street-level advertising had already built up Black Friday hysteria, and I couldn’t imagine what would happen on the day itself. I planned to wander around Escazú, making a slow circle through the district, observing rabid shoppers as I went. I imagined shrieking housewives, pulled hair, weeping innocents shoved to the ground. Paramedics would idle outside the malls, waiting with gritted teeth for the carnage to begin.

But it was nothing like that.

I did spend Black Friday walking around Escazú, but the day was tranquilo as could be. When I arrived at the Walmart in San Rafael, the store was no busier than usual, except for a cluster of customers in the electronics section. Wide-screen TVs were prominently displayed, and dozens more were stacked in cardboard boxes, but the atmosphere was downright subdued. I strolled down the residential streets to Avenida Escazú; the day was sunny and warm breezes made the palm trees sway. Avenida Escazú was quiet and easygoing. Shoppers toted their shiny new bags and zigzagged through high-end clothiers, but the scene was stress-free.

When I reached Multiplaza, I saw the gridlock traffic outside, the parking lots busy with cars and guachimanes. But inside the mall, everyone looked unperturbed. Indeed, Multiplaza was filled with people, many of whom lined up in front of stores, but they looked genuinely content, as if shopping were the easiest thing in the world. In front of Victoria’s Secret, six women tinkered with their phones as they waited to be admitted. In the top level, the food court buzzed with activity, and hardly a free table could be found – but that’s how it always is at lunchtime in Multiplaza.

I couldn’t believe I was seeing: Black Friday busyness without aggression. It occurred to me that Avenida Central functions the same way. These stores may be crammed with people, but vendors are not forceful. They don’t scream prices at you or shove gewgaws in your face. They don’t follow you for blocks or find ways to lasso you into interminable haggling sessions. Indeed, Fourth Avenue is not an Egyptian souk, and Multiplaza isn’t an Urban Outfitters at 3 a.m. If I hadn’t known it was Black Friday, I might not have noticed anything out of the ordinary. You might call it a Christmas miracle.

•

“I went to Mercado Central recently,” said my editor, Katherine, when I mentioned my little experiment. “I haven’t been in there in years. I was walking around and thinking, ‘This place is great. Why don’t I come here more often?’”

I also pass Mercado Central, that antique marketplace in the middle of San José, almost every weekday. But stepping into Mercado Central is a commitment, because the passageways are narrow and it’s easy to get lost in the maze of shops. I know how tempting it is for the most ambivalent shopper to spend hours among its stalls. Yet Katherine reminded me that I should wander through and survey the goods. Of all the places in Costa Rica, Mercado Central was the most likely to pique my interest. It is this kind of market, with its heaps of bags, textiles, cutlery, and novelties, that most excites my imagination. I might find a crockpot or machete sheath in any store, but Mercado Central makes shopping feel archaeological. You don’t just find things; you discover them.

After a quick promenade, I realized I should head to work. I stumbled into a final shop, almost by accident. I saw cowboy hats and model oxcarts, hunting knives and wooden plates. None of them interested me. They were the objects I could find anywhere, in almost any souvenir shop in Costa Rica.

But then I saw a row of objects hanging from the ceiling. They were colorful and beautifully crafted. They reminded me of something I had hoped to learn for a long time. I asked the saleswoman where they came from.

“We know a family of craftsmen in San Isidro,” she said with a mix of nonchalance and pride. “They make them there. They’re very good quality.”

All at once, I knew what to give my wife for Christmas. We don’t usually trade gifts, but I felt a flash of inspiration. In all this time ambling through San José, I hadn’t taken any of its merchandise seriously. My curiosity was academic, not practical. I had already given the painted masks and hand-woven hammocks that foreigners are expected to give their families for Christmas. I hadn’t expected anything to jump out at me.

But that’s the thing about San José: Love it or hate it, the city is full of surprises.