Jean-Claude Duvalier, the second-generation “president for life” who plunged one of the world’s poorest countries into further despair by presiding over widespread killing, torture and plunder, died Oct. 4 at his home in Port-au-Prince. He was 63.

He had a heart attack, his lawyer, Reynold George, told the Associated Press.

Despite a brief, hopeful window when it appeared that the overweight, overwhelmed dauphin might liberalize the country, the younger Duvalier soon followed in his father’s violent footsteps. Tens of thousands of Haitians were killed under the regimes, with many more tortured, according to human-rights groups.

Duvalier maintained his father’s well-established terror apparatus — most notably the Tontons Macoutes, the shadowy militia whose name means “bogeymen” — and added new techniques for skimming hundreds of millions of dollars from the national treasury.

Under the younger Duvalier’s watch, Haiti became the Western Hemisphere’s epicenter for AIDS, as well as a major cocaine-trafficking stop. Although he courted the United States and other donors with promises of human-rights reforms and a business-friendly economic policy, living conditions for Haitians dipped even lower than their already dismal standing.

Illiteracy rose and life expectancy sank. When tens of thousands of desperate, malnourished “boat people” tried to flee Haiti for U.S. shores during the 1970s and ’80s, Duvalier’s response, true to form, was to demand kickbacks from their unscrupulous human smugglers.

By the time he and his family boarded a U.S. Air Force cargo plane and flew to exile in 1986, with truckloads of Louis Vuitton luggage and millions of dollars in Swiss bank accounts, Duvalier had cemented his country’s status as the basket case of the Americas.

He remained unrepentant.

“I got to know Duvalier as a man who is by turn intellectually dishonest, manipulative, even downright clueless,” wrote Haitian-born journalist Marjorie Valbrun in a 2011 Washington Post essay, which recollected interviews she had conducted with Baby Doc in 2003.

“In rare but telling moments, he also seemed deeply sad,” Valbrun added. “He denied any past wrongdoing. He rejected accusations of corruption during his presidency. He dismissed allegations of officially sanctioned murders and arrests of political opponents as fictional creations of a biased news media. He never uttered a word of remorse and ceded only one major mistake: ‘Perhaps I was too tolerant.’ ”

According to official records, Jean-Claude Duvalier was born July 3, 1951. He was the only son of Simone Ovide and her husband, the doctor Francois Duvalier.

Francois Duvalier came from a lower-middle-class background. But, unlike most Haitians, he was educated. His father had scraped together enough money to send him to a prestigious high school, and afterward he studied medicine. He graduated in 1934, the same year that U.S. Marines, who had occupied Haiti since 1915, left the country.

Francois Duvalier, like many Haitians, had deeply resented this foreign occupation. Although he later worked with U.S.-sponsored public health programs, helping cure Haitian peasants of tropical diseases and earning the nickname “Papa Doc,” Duvalier’s experiences with the often-racist Marines helped push him to the intellectual movement known as Négritude. He began to study voodoo, Haiti’s native religion, and encouraged black Haitians to take back the power long held by the country’s mulatto elite.

Haiti descended into political chaos when the U.S. withdrew, with a dizzying array of governments, coups, power grabs and military maneuvers. Papa Doc became minister of public health and labor in one administration, only to leave office in 1950 after another military coup. He went into hiding in 1954, but emerged two years later to run for president after the ruling government forgave political opponents.

After a year of political deal-making, as well as allegations of voter intimidation, Francois Duvalier was elected president of Haiti. He moved his family into the presidential palace and began constructing a merciless security apparatus to remain in power.

He cracked down on human rights, sending potential rivals into exile or throwing them or their children into the gruesome Fort Dimanche prison, where they were often tortured to death. He encouraged his militia to terrorize civilians with abductions, beatings and extortion, and he intentionally dressed as Baron Samedi, the voodoo spirit of death. He designated a torture room in his palace and drilled peepholes into the walls so he could watch the horror.

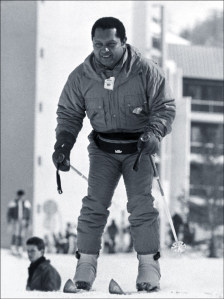

Jean-Claude grew up without much interest in the inner workings of the palace. He used the presidential courtyard as a racetrack for his tricycle, and later for his Harley-Davidson. On his million-dollar yacht, he partied with other sons of the Haitian elite — many of whom called him “baskethead” behind his back, both for his size and for his lack of intellectual interest.

When Papa Doc, long ailing from heart problems and the aftermaths of a diabetic coma, announced that he expected his son to be Haiti’s next “president for life,” the younger Duvalier said his politically minded sister, Marie-Denise, should fill the role instead. But Papa Doc’s will was law.

In February 1971, officials announced that the Haitian people had endorsed the selection of Baby Doc as successor, 2,391,916 to zero. Two months later, on April 21, the 64-year-old Papa Doc died. Jean-Claude Duvalier took control of Haiti.

Most pundits thought he wouldn’t last the year. There were jealous ministers, would-be assassins and plotting palace guards. The government was also in need of funds. Although the elder Duvalier had used anti-communist rhetoric to stay in the United States’s graces, his human-rights violations had many years earlier convinced the Kennedy administration to cut foreign aid to Haiti.

But Jean-Claude surprised the naysayers. He put a friendlier mask on Duvalierism as his family and advisers competed for the power behind the throne. He opened the palace to journalists and started paying the country’s debts. He supported a quickie divorce law — anyone could get a decree in 24 hours — that helped spark a tourism boom. He launched reforestation campaigns and became astute at cleaning up prisons right before international observers visited.

Duvalier also opened up the country to foreign business — an economic liberalization policy he eventually dubbed “Jeanclaudism.” This meant new opportunity for U.S. businesses, which soon took advantage of Haiti’s cheap labor and union-squashing Macoutes.

All of this pleased the U.S. government, and within the first few years of his rule, foreign aid increased by more than 800 percent.

The Haitian people, however, were becoming ever more desperate. Duvalier and his cronies stole most of that aid money and began a style of embezzlement shocking even by Haitian standards. Peasants and unemployed city-dwellers starved as Duvalier and his friends threw lavish parties; bought houses, sports cars and yachts; and spent millions of dollars on shopping sprees.

The extravagance hit a peak in 1980 when Jean-Claude married Michele Bennett, a mulatto divorcee with a scandalous reputation and expensive tastes. Their wedding made the Guinness Book of World Records for its immoderation. It cost $3 million, with gowns and hairdressers imported from Paris, a $100,000 fireworks show, and rum for the masses.

Styling herself as Haiti’s Eva Perón — Argentina’s populism-spouting first lady of the 1940s and early 1950s — Bennett started hospitals and charities, all funded by misdirected aid money, or from the “donations” of terrified business owners.

Some called Baby Doc’s marriage the beginning of his downfall. Not only did Bennett disgust Haitians with her decadent displays of wealth and corruption, but the marriage marked a renewed dominance of the country’s mulatto elite — an offense to many who had supported Papa Doc’s black-power ideology.

Meanwhile, the emergence of AIDS killed Haiti’s tourism industry. Business faltered because of widespread corruption. Human-rights violations were rampant. Members of Bennett’s family were linked with cocaine trafficking.

With corpses of desperate Haitians washing up on Florida’s beaches, and human-rights groups pointing out continued torture, the United States scaled back again on foreign aid. Canada labeled Duvalier’s government a “kleptocracy.” And when Pope John Paul II visited the country in 1983, he chastised the government, announcing to hundreds of thousands of Haitians, “Things must change here!”

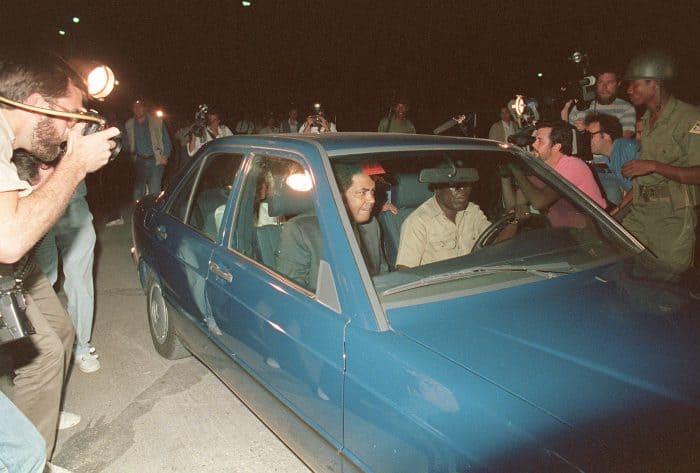

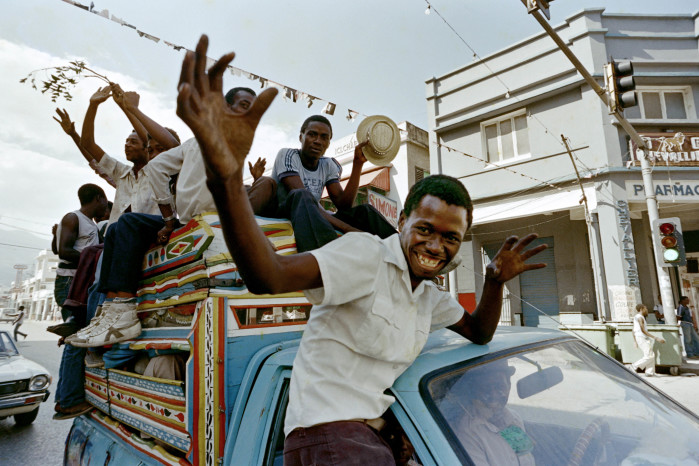

Two years later, Haitians began to revolt. Protests against the government started in the northern city of Gonaives and spread across the country, with violent demonstrations and raids of food-distribution warehouses. In February 1986, with the Reagan administration pressuring Baby Doc to leave office, and Haitian army officials telling him that he had no choice, Duvalier and his family decided to flee.

They frantically packed what they could, stuffing jewels and artwork into designer luggage, and shortly after 2 a.m. on Feb. 7, 1986, drove to Francois Duvalier International Airport, where a U.S. Air Force C-141 was waiting to take them to France.

“People viewed him as their vehicle for power and wealth, so therefore they supported him,” said Robert Maguire, a Haiti specialist at the U.S. Institute of Peace. “In the end of his regime, things got very shaky because there was so much stealing, so much accumulation of wealth, and because the life of the Haitian people had gone downhill so far that there was unrest.

“He lost the support of his father’s grass-roots supporters because they resented him giving power to the mulattos,” Maguire said. “He ended up governing in a very shaky way, and then his regime collapsed quite suddenly.”

Although the French government officially refused to accept them, the Duvaliers settled into exile on the French Riviera. According to Time magazine, Baby Doc passed the time by driving his red Ferrari back and forth to Cannes, while Michele did crosswords and ordered designer clothes. Meanwhile, back in Haiti, citizens took deadly revenge on members of the Tontons Macoutes, and the cycle of violence, coups and repression began anew.

Michele and Jean-Claude divorced in 1993, with much of their money still frozen in Swiss bank accounts. Survivors include two children.

In January 2011, Jean-Claude Duvalier surprised Haitians by returning to his earthquake-damaged country with his companion, Veronique Roy. The frail-looking Baby Doc said that he was not there for politics, but because he wanted to “help.” Banking experts, however, suspected that he had arrived to circumvent new Swiss regulations preventing exiled leaders from obtaining money stolen from their countries.

He was promptly arrested and charged with embezzlement and other crimes, but remained living in a high-end hotel in the mountains of Port-au-Prince.