A quarter of a century ago, when President Oscar Arias was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize as chief architect of the Central American Peace Plan, my husband, Tony Avirgan, and I were among a handful of international journalists based in Costa Rica. We chose to move to Costa Rica largely because we admired its strong commitment to non-militarism, democratic institutions and economic equity.

Although the United States claimed to be promoting these values, sadly, we found that U.S. policies in the 1980s were undermining Costa Rica and pulling the country into the cauldron of conflicts in Central America.

In reflecting upon this distant period, the Peace Plan stands out as a remarkable victory. It represented a clear line in the sand drawn by the five Central American presidents who, in defiance of Washington, agreed to negotiate an end to the isthmus’ various conflicts.

Over the preceding five years, we and others had seen Costa Rica readied to serve as the Southern Front of the U.S.-backed Contra war against Nicaragua. When Luis Alberto Monge became president in 1982, the Reagan Administration offered a deal he wasn’t able to refuse: U.S. economic assistance in exchange for use of Costa Rica in the Contra war. Aid started to flow, and within a few years, Costa Rica became the second-highest per-capita recipient of U.S. economic assistance – surpassed only by Israel.

The Southern Front, an alphabet soup of tiny Contra armies, was loosely united under the command of Edén Pastora, a former Sandinista military hero. Both the Reagan and Monge administrations officially denied the existence of the Southern Front and proclaimed that Costa Rica’s “unarmed neutrality” was being respected. But for those of us living in Costa Rica, signs of the clandestine Contra military and CIA operations were not hard to find.

In March 1984, Tony and I helped produce an explosive series that ran simultaneously on ABC TV and in The New York Times. We revealed that Pastora’s military headquarters and radio station were based not “in the mountains of Nicaragua,” but rather in a large house in the hills of Escazú, southwest of San José. An embarrassed Costa Rican government quickly raided and officially closed Pastora’s Escazú headquarters. For us, this meant that Tony and I became personas non grata with the Reagan administration. U.S. Ambassador Lewis Tambs publicly called us “traitors.”

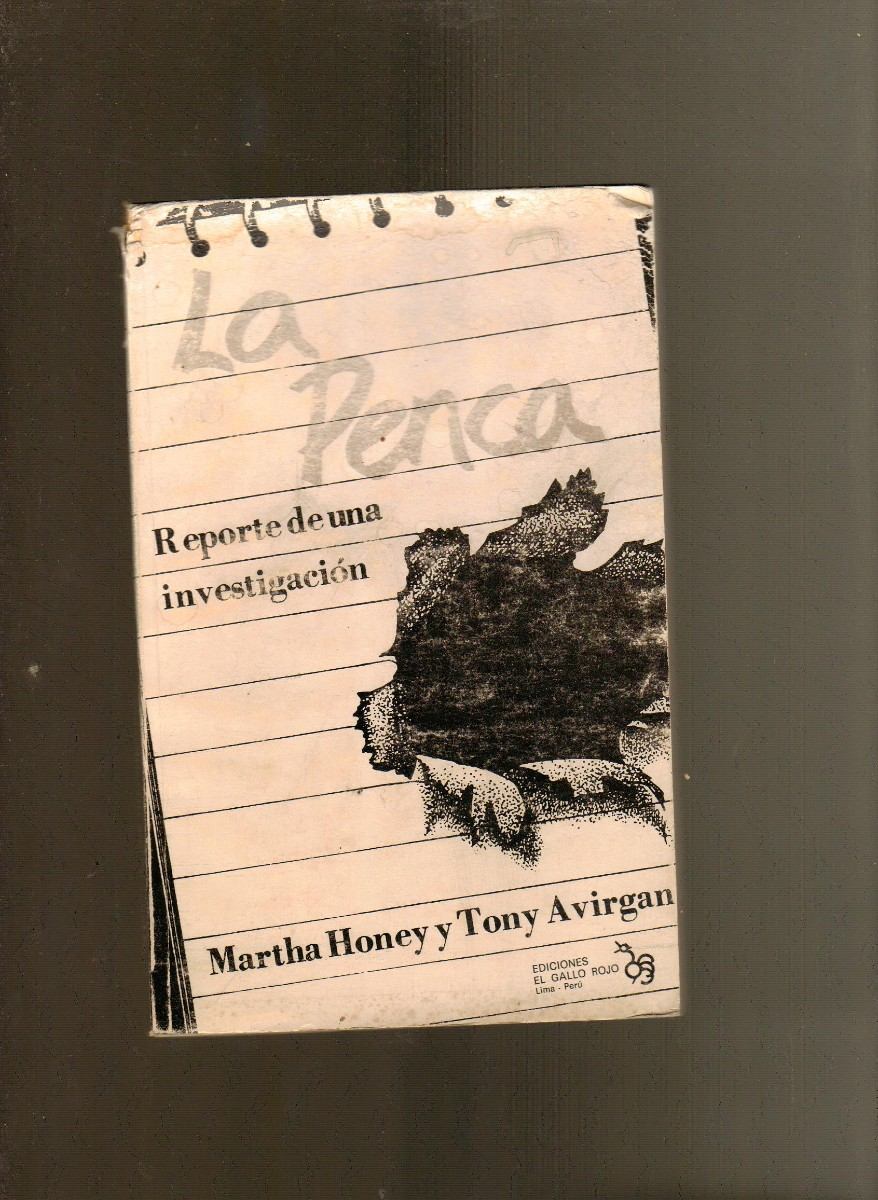

The La Penca bombing, on May 30, 1984, altered our personal and professional lives forever, along with the lives of many others in Costa Rica’s press corps. Tony, who was on assignment for ABC TV, was among the several dozen journalists who traveled to Pastora’s press conference at a one-hut Contra encampment on the Nicaraguan bank of the Río San Juan.

The La Penca bombing took the lives of three journalists – Costa Ricans Jorge Quirós and Evelio Sequeira and American Linda Frazier, who worked for The Tico Times. Seventeen others were injured, many very seriously. Our close friend Roberto Cruz would die years later, in large part from his wounds.

Like other family members, I rushed to the San Carlos hospital where the La Penca bombing victims were being brought. Finally, at dawn, Tony arrived in the last ambulance. He was covered with shrapnel wounds, but as he smiled faintly at me, I knew he would live.

Several days after the bombing, I was contacted by two U.S.-based journalist associations and asked to undertake an investigation into who was responsible for the La Penca bombing. We did not foresee that in the process of investigating this terrorist bombing we would stumble upon a much larger criminal enterprise, the Iran-Contra scandal.

The evidence initially assembled by us and our colleagues, as well as Costa Rica’s judicial prosecutors, pointed to a covert network being run by National Security Council official Col. Oliver North, and involving John Hull, a group of anti-Castro Cuban-Americans, a team within the U.S. Embassy, collaborators in the Costa Rican government, and FDN Contra officials. In the course of our investigation, we received death threats, had one key witness murdered and were forced to protect another by arranging for him and his family to flee Costa Rica for exile in Canada.

In mid-1985, we published our initial findings accusing Hull, Cuban-American Felipe Vidal and others of carrying out the La Penca bombing and using Contra supply planes to traffic cocaine from Colombia to the U.S. Hull retaliated by suing Tony and me in Costa Rica for libel and defamation of character. In May 1986, we managed to turn the tables by presenting a string of courageous witnesses who told the hushed, packed courtroom details of covert CIA and Contra operations in Costa Rica. The judge completely absolved Tony and me of all charges. As the courtroom erupted in applause, a grim-faced Hull quickly left, vowing, “This isn’t over yet.”

However, the political tide was about to turn. That same month, the Arias government took office, and it was, we felt, a breath of fresh air. The administration, we came to realize, was determined to uphold Costa Rica’s core values of neutrality and non-militarism by closing down the Southern Front. Arias advisor John Biehl recalled later that Arias became “very angry” as he was briefed by U.S. Embassy officials on their extensive covert operations inside Costa Rica. “He never thought things had gone so far,” Biehl said.

Arias himself said in an early interview that he was motivated not by fear of a Sandinista invasion, but rather by fear that unless the anti-Sandinista operations were disbanded, Costa Rica would end up fighting the Contra forces. One of Arias’ first actions was to privately tell U.S. officials he was closing a secret Santa Elena airstrip that had been built by North’s network to help resupply the Contras.

On July 4, 1986, Minister of Natural Resources Álvaro Umaña and First Lady Margarita Penón first flew over the dirt airstrip that was next to the Santa Rosa National Park, in the northwestern province of Guanacaste. When, over the next months, park officials reported sighting large cargo planes circling the airstrip, its presence was “discovered” by the international press.

Arias, whom North’s diaries reveal was referred to by U.S. officials as “the boy,” managed to snub CIA head William Casey by refusing to meet with him when he arrived unannounced in San José. And, during Arias’ tenure, Costa Rica’s Legislative Assembly carried out investigations that implicated North, Hull, the U.S. ambassador and CIA station chief, and others in Contra-related drug trafficking and other “hostile acts” against Costa Rica. Judicial authorities reopened the stalled La Penca investigation, ultimately bringing murder charges against both Hull and CIA operative Felipe Vidal. Both fled the country.

However, unanswered questions about the La Penca bombing have continued to haunt us. Through the ’80s, all serious investigations of the bombing had pointed to the CIA, but we had not discovered the true identity of the bomber.

In 1993, we were shocked when Swedish journalist Peter Torbiörnsson finally confessed to us that he had been collaborating with the Sandinista Security Ministry and had brought the bomber known as “Hansen” to La Penca at the request of the Sandinistas (TT, Sept. 16, 2011). Other journalists managed to identify the bomber as a leftist Argentine guerrilla name Vital Roberto Gauine. He was part of a “special operations” unit, known as the Fifth Directorate, which was run by a top Cuban intelligence agent, Renán Montero, and Sandinista Interior Minister Tomás Borge.

Despite such lingering questions, it is now, at this quarter-century mark, important to commemorate the crucial role of the Central American Peace Plan. As the Nobel Committee forecast, this plan paved the way for ending the region’s wars and transitioning to largely democratic elections.

While real political stability and equitable development has continued to elude much of Central America, the Peace Plan remains a significant milestone. Arias showed that strength and security could come through dialogue and disarmament, rather than through waging war.

He demonstrated that the leader of a tiny country located within what the U.S. calls its “backyard” could craft an independent diplomatic strategy without Washington’s approval. In pursuing a regional peace plan, Oscar Arias took the best of Costa Rica’s traditions – its commitments to peace, social and economic justice, and rational discourse – and elevated them to the level of international diplomacy.

Martha Honey and her husband, Tony Avirgan, worked as international journalists in Costa Rica from 1983-1993. Martha is currently co-director of the Center for Responsible Travel, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., and affiliated with Stanford University. Martha’s book, “Hostile Acts: U.S. Policy in Costa Rica in the 1980s,” carries a full account of the topics in this article.