Years ago, back in his native England, a young Michael Brennan was working as a grunt for The Croydon Times. He liked the job and working for a newspaper, but he had always fancied himself a proper reporter. One day, he asked a higher-up employee what his prospects might be writing for the paper.

I don’t think you have the intelligence to be a reporter, said the man bluntly. You can be a photographer.

He was 21 years old and had grown up in working-class Sheffield. He had never handled a serious camera in his life. He couldn’t afford the Rolleiflex that he coveted, so he ended up buying a cheaper Yashica. He fiddled with the camera on his own, and colleagues gave him basic instructions, but Brennan didn’t study in a regular classroom. He didn’t take workshops or go on photo-walks. He dove headfirst into the trade, snapping pictures for The Croydon Times, then The Sunday People and The Daily Herald. He worked his way through the ranks, photographing a wide range of subjects.

In 1967, Brennan found himself on the edge of a large body of still water in England’s Lake District. He was supposed to witness the pilot Donald Campbell as he attempted to break the water speed record in the hydroplane Bluebird K7. The day was expected to be historic, but it took a tragic turn. Campbell launched forward, slowed, then turned around, hoping to make a second attempt. The hydroplane lifted off the surface and crashed into the water, killing Campbell and wrecking the vehicle.

Brennan took a quick burst of pictures as the hydroplane crashed. He felt confident that he had captured something, though it was impossible to say what he had culled from the seconds-long cartwheel. When the pictures were developed, Brennan discovered he had taken three perfect shots: the hydroplane in midair, then smashing into the water.

The photos appeared in LIFE magazine. Brennan won the British News Picture of the Year Award.

Today, he is among the most acclaimed living photographers in the world.

•

Brennan lives with his wife Lily in a brightly lit house near San Rafael de Heredia. He is a graying and compact man who has aged gracefully, so that it is easy to imagine him younger. When we arrive to talk, he and his wife make a round of tea and coffee.

“What can I do for you?” he says pleasantly.

Well, he doesn’t say the words so much as whisper them. Brennan has struggled with throat polyps for several years, some of which have metastasized. His doctors are certain that he will make a full recovery, but for now he must speak in a soft rasp and await the inevitable rounds of radiation. He is familiar with this situation. His own father, an “Irish immigrant taxi driver” in Yorkshire, succumbed to cancer after years of smoking. However, Brennan keeps a stiff upper lip. If he is concerned, he expresses this through eye-rolling and dismissive humor. The man schlepped his way through Pakistan and Northern Ireland during some of their darkest periods; he seems perfectly equipped for this.

“I’m retired,” he says. “Not by choice, but by circumstance.”

For decades, Brennan worked as a freelance photographer. He shot pictures throughout the 1960s, photography’s golden years, when gazing at magazines like LIFE and Sports Illustrated was as reasonable a pastime as television. When he had the chance, he traveled to exotic countries, but such trips could be pricey for a man paying his own expenses, so he frequently photographed gallivanting celebrities when they returned home.

Brennan’s memory is impeccable: He particularly remembers May 10, 1985, a blazing hot Sunday evening in New York City, where he lived and worked for many years. The day was so sultry that it was insufferable to stay in an apartment without air conditioning, so he decided to head for a bar. Brennan has a long history with pubs, having aggressively toured the nightlife of northern England, and a lazy Sunday evening seemed ripe for socializing. When he arrived, he noticed a woman speaking with a Spanish accent. She was beautiful enough to be a model – and had almost become one, thanks to some training at Barbizon Modeling School – but now she worked for the cosmetics section of Bloomingdale’s. She had been living in New York for about 20 years. Her name was Maria Yalile Martinez, but friends called her Lily.

“It was as easy as that,” says Brennan.

“Not that easy,” Lily counters. Then she smiles. “I lived with my grandmother.”

At some point, Brennan asked her where she was from.

“Costa Rica,” Lily said.

•

They got married, and for a long time Brennan continued to work for any newspaper or magazine he could get his hands on. After the couple’s move to Blairstown, New Jersey, the photographer found a niche in New York; strangely, he was one of the few foreign correspondents working in the city, because most British papers acquired their photos from U.S. wire services.

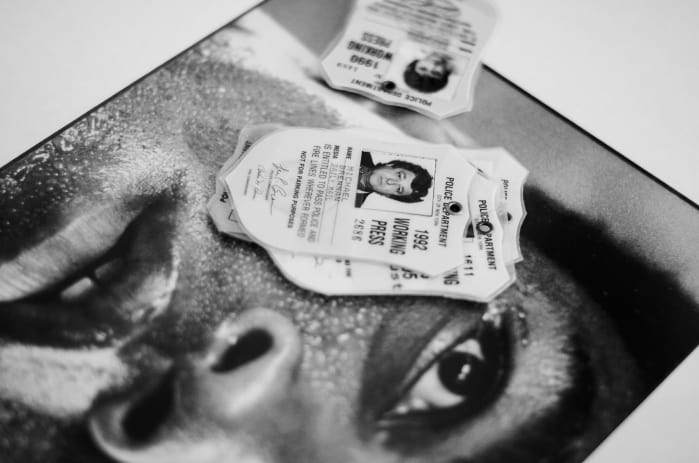

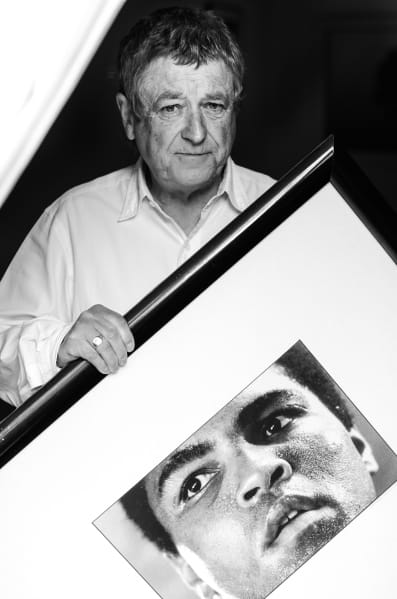

Brennan’s working life was a constant hustle. At a moment’s notice, he might head over to Pottstown, Pennsylvania, where he would call on Muhammad Ali. The most famous boxer in the world had a training facility in Pottstown, and Brennan had cultivated a friendship with Ali, who enthusiastically posed for portraits. Brennan remembers Ali in a singular way – a playful man who had struggled through poverty, since race-conscious sports companies had declined to sponsor him – and although Brennan has never been a boxing fan, he loved to photograph the warm-ups, the fights, and the fights between the fights. (During a Mike Tyson bout, Brennan was knocked down from the ring, camera in hand.) Ali and Brennan have remained friends to this day, despite Ali’s severe dementia.

“Every day was different,” Brennan recalls. “Every day was fun.”

Brennan is humble and friendly, and he tells stories with the enthusiasm of a castaway rescued from a deserted island. But unlike a barstool raconteur, Brennan will stop, light up, and trundle toward a back room, where he pulls out a photograph to illustrate the moment. Some of these are snapshots, but others are globally recognizable images: He shows a picture of Mother Teresa in Calcutta, a petite, wizened woman among her flock.

“She was a pain in the ass,” says Brennan. He pauses, shakes his head, and adds, “She really was.”

Brennan is quick to add that he greatly respects Mother Teresa’s work, but he also found her agitated, dismissive, and frustrating to interact with. This is one of the great luxuries of Brennan’s life: Not only did he photograph his subjects, but he often saw the flip sides of their lives. He sometimes traveled in private jets with rock stars and watched their wildly destructive antics; at one point, one of the most famous musicians in the world threw a cup of vomit at him. (Brennan requested not to name said musician, because he is “famously litigious.”)

Brennan abhorred – and still abhors – the paparazzi, and although he spent much of his time tailing famous personalities, most of his interactions were brief and purposeful.

“They shouldn’t be called paparazzi,” Brennan spits. “They’re just thugs, really. And they really devalue what we do.”

One of Brennan’s most unique relationships was with John Lennon, whom he photographed and often saw in the streets of Liverpool but was never close with. Here is one of the peculiarities of an English life in the 1960s: Brennan and Lennon actually shared mutual friends. They had grown up under similar roofs. Given the chance, they could likely have banged on for hours about shared perspectives. The portraits that Brennan took of Lennon speak as much as a close friendship could have, as do so many of Brennan’s pictures of so many people. In an instant, Brennan seemed to capture the spirit of a person, whether he knew them well or not. It was this intimacy that made him famous.

Then, as one millennium melted into another, work grew thin.

“The business went down the tubes,” says Brennan. “We had a few nice years there. Most everyone in England knew who I was. Germans were just great to work for. It was wonderful. But I did not take to digital very well.”

In this sense, Brennan’s story is painful but typical for the field: Publications lost sales, scaled back, and closed altogether. Online publications didn’t want to pay the same fees as print. Dependable editors shuffled around or retired. Brennan invested in digital cameras and adapted, taking some notable shots with a DSLR, but he wasn’t keen on the changing environment.

After a time, Brennan and Lily retreated. Lured by tropical weather and a simpler way of life, they moved to Costa Rica.

•

For Brennan, Costa Rica is not so much a place as an era in his life. He doesn’t take pictures. He has his old cameras, but all of them are broken or unusable. This is Lily’s homeland, but she had lived in the United States for decades, so it is nearly as foreign to her as to her husband. The couple has a splendid house, which is decorated with a range of vintage prints. He has a sizeable office with a wide-screen desktop computer, the text enlarged to accommodate his fuzzy eyesight. Their house stands on a quiet and wooded street, a pleasant place to retire. He has found Costa Ricans friendly and generous, and he particularly praises his doctors, who have gone to great lengths to care for him.

Brennan has never had an interest in teaching. He has accepted awards but doesn’t imagine himself on a lecture circuit. He admires contemporary photographers, particularly the young bucks starting out, but he also feel sorry for them – the low pay, the increasingly dangerous assignments. He knows that he can’t really return to that world, now that it is in a global tailspin. Brennan seems adrift between purgatory and paradise, content with the company of his wife, his enormous dog, and a great deal of fresh air.

But there is something simmering in Brennan, and it is clear that the man will not simply fade away. He has spent an enormous amount of time poring over his photos, an archive so colossal that he can’t even estimate how many shots he took. While the job itself has vanished, Brennan has something few others have: a pictorial record of his existence, a kind of autobiography of the scenes he has witnessed, an epic told in scattered milliseconds.

This past week, an art gallery owner in Los Angeles named Chris Forney opened an online store for Brennan’s works. The photos that have mesmerized their creator for the past few years have become publically available – not as novelty mugs or dorm room posters, but as works of art. Brennan is uncertain what his prospects are, but he is quietly ecstatic that Forney has given his photographs such respectful attention. Nearly anyone in the world can order one of his prints. For Brennan, this costs nothing. He can wait for people to visit the website, to join him in gazing at his work.

The fire is clearly still there. Prompt him to talk about life in the field, and he starts getting passionate. His speech is more excited than his fragile voice can handle.

What was lost when the Golden Age of Photography ended?

“What ended was the excess,” says Brennan. “Editors would think nothing of sending a team of guys to Africa to photograph cheetahs. But you’ve got to be practical about it. I couldn’t afford to be precious. That’s the beauty of journalism: You stick to the storyline. It’s always been my mantra – you’ve got to get it done and get it done quickly. You have to pay your rent.”

He ponders for a moment, glancing at a corridor full of framed photographs, the same photographs that millions of people have also seen throughout the years, and by seeing them, have broadened their understanding of the world.

“I’m bloody lucky,” Brennan says. “You’ve got to have a lot of luck.”

To see Brennan’s portfolio, visit his new website.