The strangler fig is one of the most iconic trees of Costa Rica. They’re present throughout most of the country’s varied landscapes, their life history is fascinating, they’re a food source and home to a huge variety of wildlife species, and they’re just begging to be climbed. Let’s learn a little more about strangler figs.

Strangler fig isn’t the name of a single species of tree, but a common name applied to many different but related species in the genus Ficus and the family Moraceae. I tried to find the number of species that call Costa Rica home, and I ran across the number 50 a few times, but those articles didn’t scream “I was written by a scientist!”, so take that number with a grain of salt. In Spanish, the many species of strangler fig are commonly known as matapalo and higuerón.

Strangler figs occur naturally through most of Costa Rica’s habitats including low and high elevations and wet and dry regions. They’re commonly planted by people as ornamentals, as living fence posts, and as shade trees for cattle. I live in a town called Matapalo, named after the matapalo trees that once lined the plaza which were cut down long ago. It’s a common name for villages throughout the country, named after a towering tree or group of trees that were found or still can be found around town.

Strangler figs can grow into enormously tall and wide trees. How they go about arriving at such an impressive mature state is an interesting story. Their lives begin as sprouting seed which has recently been ‘deposited’ among the branches of a host tree by one creature or another which recently enjoyed eating some figs. For now, this young tree is an epiphyte, a plant which grows on the surface of another plant.

As it matures, it grows long roots which descend down the host tree, eventually reaching the soil. After the first roots reach the soil, the plant sends down more and more roots which eventually begin to grow in diameter and interlace amongst themselves, often fusing together.

As time passes, the strangler fig completely envelopes the host tree. Its canopy begins to shade out the host tree’s canopy, its latticework of roots restricts the growth of the host tree’s trunk, and its roots compete with the hosts tree’s roots for nutrients in the soil. Usually, with enough time, the host tree gives up the ghost and eventually rots away leaving a strangler fig tree with a hollow interior in its wake.

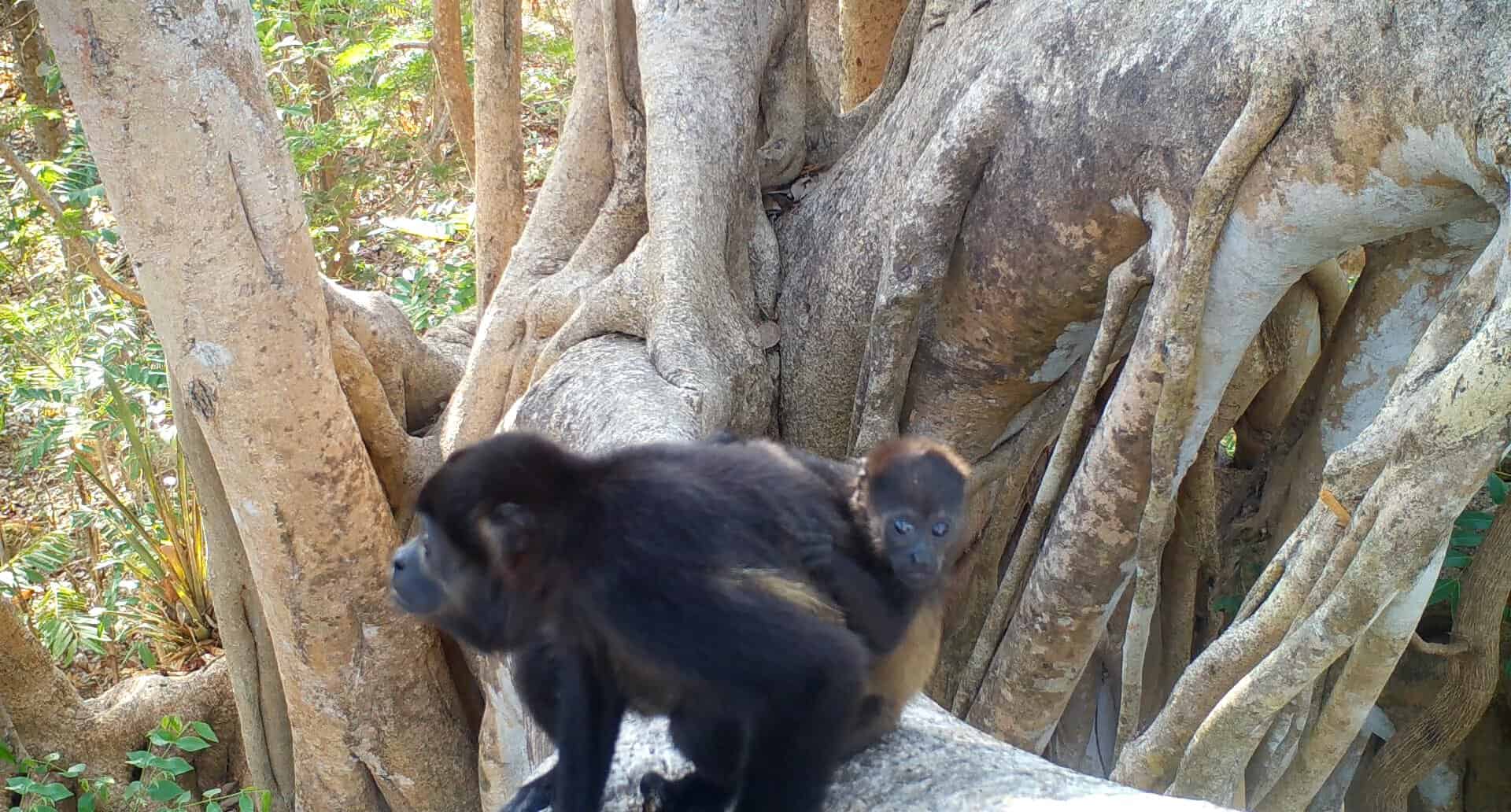

While it could be considered a bit of bummer that the strangler fig kills other trees (matapalo literally translates to ‘tree killer’), I believe these trees more than even the scale in the balance of life versus death. For one, they feed an incredible variety of wildlife. A huge number of species of birds, reptiles, and mammals, including a ton of bats, feed on the fruits of the strangler fig. On top of that, the intertwining root system that makes up the trunk and the hollow spot left behind by the host tree gives wildlife one million little places to sleep, nest, hide from predators, and look for prey. Each tree is like an entire ecosystem, hosting huge numbers of other species.

Since each tree provides both food and shelter for such a wide variety of species and because their tangled trunks look like every kid’s dream of a climbing tree, strangler figs are excellent places to put camera traps. I’ve had the opportunity to place cameras in strangler figs on multiple properties, and each time I’ve been rewarded with videos featuring a wide variety of species.

The only issue with camera trapping these trees is that each tree inevitably hosts several species of wasps which make their homes amongst the tangle trunk and do not appreciate being disturbed by a guy scrabbling by the entrance of their nest with a backpack full of cameras. I have been stung a few times and once had to leave the camera and jump out of a tree while being attacked by honeybees, but it was worth it to share the wildlife clips in the video below.

About the Author

Vincent Losasso, founder of Guanacaste Wildlife Monitoring, is a biologist who works with camera traps throughout Costa Rica. Learn more about his projects on facebook or instagram. You can also email him at: vincent@guanacastewildlifemonitoring.com