This article is excerpted from Tom Shroder’s “Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy and the Power to Heal,” which comes out Sept. 9. The book focuses on researchers’ attempts to determine whether psychedelic drugs administered with talk therapy can help people with post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric ailments. Such studies flourished in the 1950s when more than 25,000 doses of psychedelic drugs were administered to thousands of patients and the accepted assessment held that the drugs would be “of utmost value in psychotherapy.”

Rampant recreational drug abuse in the ’60s provoked government restrictions on research, but a small group of scientists persisted in the belief that psychedelic drugs were too potentially valuable to be discarded. In the past decade, a number of clinical trials have won approval at major research institutions, including Johns Hopkins.

These studies have shown promising results using MDMA, psilocybin and other psychedelics in controlled clinical settings under close medical supervision, even as abuse of drugs sold on the street as psychedelics continues to claim victims.

•

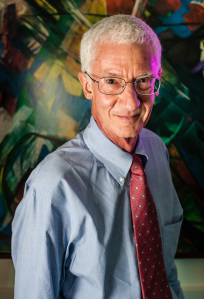

Roland Griffiths, a slender man with a thatch of white hair and piercing eyes, got his PhD in psychopharmacology in 1972 from the University of Minnesota, then went to Johns Hopkins’ Behavioral Biology unit, where he specialized in determining the relative abuse potential of drugs.

Griffiths became a recognized expert in his field, was happy and successful in his work. In his personal life, he discovered meditation, and that changed him in a fundamental way.

“I had remarkable experiences that were unlike anything else I had had. … And all of a sudden, for lack of a better descriptor, it opened a spiritual window in the world for me,” he said.

At some point, a light went on in Griffiths’ mind and he realized his personal and professional concerns could converge seamlessly: He researched psychoactive drugs. A certain class of psychoactive drugs was reputed to induce just the kind of experiences he’d been so affected by in meditation. Psychedelic drugs.

“I grew up in a scientific culture that had just ruled out doing research with these compounds,” Griffiths says. “But as I just contemplated more deeply and really thought where my interests lay, I thought, ‘Well, why not?’ “

With his track record doing drug research in cooperation with the government and his sterling reputation, Griffiths won approval to do one of the first studies of the effects of psychedelic drugs in 30 years. Over the course of the study, which began in 2001 and was published in 2006, three dozen people lay on a comfy couch in an architecturally challenged building on Johns Hopkins’ stark medical campus in north Baltimore and took a naturally occurring psychedelic compound called psilocybin — the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms,” which like most psychedelics, as he had learned in his previous work, was not addictive.

“What I wasn’t prepared for,” he says, “is people would come in two months later and I would say, ‘Well, so what do you think of the experience?’ And they’d say … ‘It was one of the most important experiences in my life.’ “

In the end, more than 70 percent of the participants self-rated the experience as one of the five most important in their lives. Perhaps even more astoundingly, nearly a third rated it the single most important experience of their lives.

“My initial response was kind of disbelief. It just doesn’t sound right, does it?”

Griffiths wanted to know more. He began recruiting subjects for another study in 2008 to determine if the, for lack of a better term, religious experience induced by psilocybin could ease the anxiety and depression of those with life-threatening cancer.

The study will eventually involve 44 subjects. Three quarters of the way through it, Griffiths has found that the experience significantly reduces the subjects’ fear of death and tends to change their focus from aggressive medical treatment to enhancing the quality of their remaining life. (Researchers of earlier pilot studies at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and New York University also found psilocybin therapy promising. Charles Grob, the psychiatrist at Harbor-UCLA who conducted one study, cautioned that his conclusions were based on small sample sizes, but said his subjects had consistently positive results.)

A retired psychologist named Clark Martin saw a mention of the study online in 2008. His cancer had been diagnosed in 1990, when he was 46, the same year his daughter was born. He had a kidney removed. Four years later, doctors discovered extensive lung cancer, for which he had surgery and 11 months of chemo, followed by the discovery of three more metastatic tumors. He threw himself into researching his illness, and fighting it took over his life. He had been a passionate sailor but lost interest in that, and almost everything else, even to the point where he felt like he grew emotionally unavailable to his daughter. “I kind of got into this very narrow sort of life space,” Martin said.

But his obsession with his illness led him to the Johns Hopkins Web site, and Martin called the number he found there. He qualified for the study, and Griffiths flew him to Baltimore.

Recommended: An appointment with Dr. Iboga

After taking the drug in a comfortably appointed room, the first thing Martin noticed was that the music on his headphones annoyed him. But before he could act on it, the music disappeared. Everything began to dissolve. He felt a clutching panic as simple everyday constructs began to melt down and evaporate. He thought of falling out of a sailboat and treading water helplessly, as the boat disappeared. Then the water disappeared. And then he began to disappear.

Martin had always been about maintaining control in his life, pegging the world in neat, rational categories, everything in its place. Now he was flailing. “It’s like my entire body, my entire psyche, just wanted to get everything to fall back into place, to gel again.”

He thought that if he could get up off the couch, do something, touch something solid, maybe he could regain a sense of normality. At one point he became aware of the presence of his two “sitters,” the attendants who watched over all the experimental subjects to offer a sense of security. Martin sat up, obviously distressed. The attendants said nothing, but one put his arm around Martin’s shoulders. He felt that presence as a link to a more soothing reality. He lay back down and went deeper into the psychedelic experience, which can be astoundingly variable from person to person, and even from one time to another. Martin saw no hallucinations, had no thoughts, not even visual images. In fact, he had no sense of self — there was only a diamond-cut void where he disappeared entirely. Except something remained: an unadorned, unelaborated awareness, thoughtless, yet present.

The panic faded into tranquility. The hours that passed he would later describe in a journal entry:

“There was no experience of any ‘things’ and the mind seemed lucid and alert. It was very comfortable and somehow familiar. There was no drugged feeling. If there were any words to describe it, they might be curiosity or awe. …”

And then he had the sense he was beginning the long journey back to the familiar reality. He found himself reluctant to leave the simple clarity, so he practiced allowing himself to slip out of it toward normality, then return to the void.

“I did that, I don’t know, maybe a dozen times, because I wanted to sort of bake that into my muscle memory, so to speak, so that I could voluntarily return to that state.”

As he emerged, he began to marvel at the steady presence of the sitter who had put his arm around his shoulder, and the fact that it was his presence alone — no words, no actions other than that one touch — that had meant everything to him in his panic. He realized that he had been missing that simple fact in his most important relationship, with his daughter.

“I had an insight that my primary role as a father was to maintain a rock-solid attunement with my daughter. … The significance of this for me was that personal relationships do not need to be managed. Therefore, there is no need to present a false self and, in fact, doing so will severely limit the joys available naturally in relationships.”

When he returned to his hotel room, he was shaken. “I was scared to go to sleep because I was fearful that I would drop back into the study stage and there wouldn’t be anybody there.”

In the coming weeks the experience kept working on him. Eventually, he says, he fell into a new way of being. A year after his psilocybin experience he wrote:

“There has been a shift from trying to micro-manage life to trusting intuition and spontaneity. … I’m more focused on values and process and less likely to feel long-range goals are set in stone. I am again involved professionally and socially. Most significantly, life has continued to open up, a move away from the depression and what felt like a downward spiral. Somehow, the psilocybin re-engaged a fullness of function that had been lost.”

He had a new relationship with his daughter: Instead of an arm’s length, role-dominated father-daughter relationship, “we’re two people who share what’s going on in our lives in a very real, spontaneous kind of way.”

Another breakthrough he hadn’t considered possible came in his relationship with his father, who lived in a nursing home in an advanced stage of Alzheimer’s. Before the psilocybin, Martin had visited him out of obligation.

“I wasn’t really present,” he said. Mostly “I was … figuring out in my mind … how long will it be before I leave.”

After his psilocybin experience, he found that “I connected with him at the level that he was functioning. And he just really cranked it up, not that he can maintain a conversation but he attempted it.”

He began to see things through his father’s eyes, and felt his frustration at being so constrained, day after day, by four walls. On impulse, he gathered his father up and went driving for hours in the wide-open ranchland that surrounded the home, something he never would have considered doing before.

Now his father “just lives for those drives. He thrives on it. He’s actually gotten better physically and mentally. And I know it sounds odd, but I’ve never felt closer to him.”

“Acid Test” is published by Blue Rider Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Tom Shroder. Virginia author Shroder is a former editor of the Washington Post Magazine.