REYNOSA, Mexico – Carlos boarded a bus last month using money he earned picking coffee beans and corn, fleeing the gangs of his native Honduras who’d threatened to kill him if he didn’t join. The 17-year-old made it as far as a migrant shelter in Reynosa, Mexico, less than a quarter mile from the U.S. border, unsure of how to finish the trek.

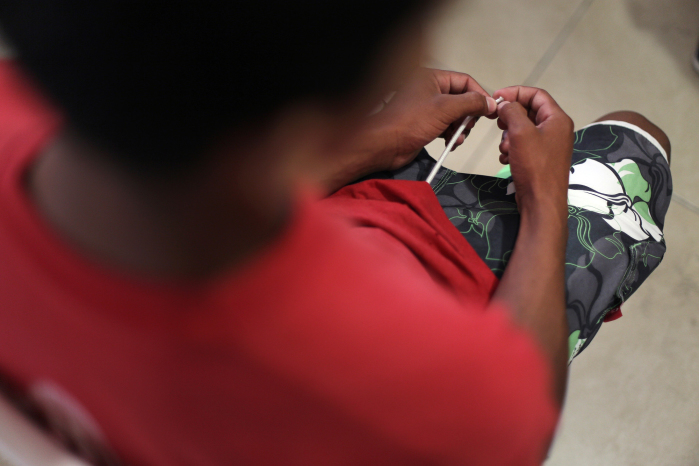

“Where I live, parents are obligated to give a son to the gangs,” Carlos said this week as he fought tears and fidgeted with the drawstring of his Hawaiian flower-print shorts at the Senda de Vida shelter. His last name is being withheld because of his age.

If Carlos makes it to the United States before his birthday next month, he will join a record flood of unaccompanied minors crossing the southern border, a deluge that began in 2011. About 52,000 have arrived since October, about 112 percent more than the entire prior year, Alejandro Mayorkas, deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, said Friday in a conference call with reporters. They’re part of a surge of immigrants, mainly Central Americans, fleeing violence and poverty after hearing that immigration policy has grown more accommodating.

President Barack Obama this month directed the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ameliorate the “urgent humanitarian situation” and asked Congress for funding. Courts and social-service agencies have been overwhelmed, and guidelines on processing and detention thrown into disarray.

The administration is increasing enforcement and deportation, Mayorkas said. That includes adding detention facilities for adults with children and sending immigration judges and attorneys to process cases more quickly, he said.

“It’s been a humanitarian crisis since long before Obama called it that,” said Kimi Jackson, director of the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project, which aids children in immigration court.

They come north by foot, bus or atop the train they call la bestia, the beast. In border towns such as Reynosa, a city of about 600,000, shelters provide transients like Carlos with beds, food and prayer.

Senda de Vida — the Path of Life — is a walled, church-run institution that spans a block, with a bleached courtyard and peripheral outbuildings: an office, dormitories with bunks and open-air areas for dining and religious services. Clothing flapped on a line as men clustered in shady spots. Two sat in pews watching Mexico play Brazil in the World Cup on a mobile phone.

Some who’ve ventured beyond the walls have disappeared in the dangerous city, people at Senda de Vida said. At the river, cartel-linked traffickers extort money from the families of those attempting to flee Central America.

“There’s such an enormous desperation to get out,” said Michelle Brané, director of the Migrant Rights and Justice program at the Women’s Refugee Commission in Washington. “Smugglers have come in to meet the demand.”

Once minors get into the U.S., they typically turn to immigration agents for protection, she said.

In 2011, officers in the U.S. Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley sector, across from Reynosa, began apprehending more Central Americans than Mexicans for the first time in years. Most come from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, where gang warfare and social and economic instability have worsened, White House officials have said.

The number of youths from those countries who were under 18 at the time they were deported decreased to 496 in 2013 from 2,275 in 2008, according to an analysis of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement data by Jessica Vaughan of the Washington-based Center for Immigration Studies.

Obama has ordered officials to coordinate a response to the crisis, providing equipment, supplies and expertise, according to a June 2 White House memorandum.

Republican critics blame the administration for lax enforcement and sending the wrong message by releasing minors and women with children from facilities unequipped to handle the volume.

The tidal wave shows no signs of stopping, and U.S. law requires children to be held pending arrangements for deportation or release.

Carlos joined the migration after his sturdy build attracted gangs’ attention at home in Olancho Department, northeast of the capital, Tegucigalpa. An uncle defied the criminals and paid with his life, the boy said.

Carlos spoke quietly and fast, with a thick Honduran accent to his Spanish, making little eye contact with interlocutors. He said he hasn’t decided whether he’ll try to reach an uncle in Houston clandestinely or voluntarily surrender to agents.

“If I do that, they could deport me,” he said. That could be fatal.

Honduras is home to the world’s highest murder rate, with 90.4 killed for every 100,000 people, according to the United Nations. About 49 percent of its citizens are younger than 20, compared with 27 percent in the U.S., according to 2010 United Nations statistics.

The increase in lone children fleeing Honduras has outpaced that of any other country. More than 13,000 have been apprehended this year, up from 968 in 2009, according to U.S. government data.

“You have to leave your family to live,” said Abraham, 16, a Honduran at another shelter, Casa de Migrante.

Abraham said he and a 28-year-old cousin, Nery, left under cover of the night. Nery, who wept at a photograph of his daughter, Daisy, 5, wore a black T-shirt with an image of Homer Simpson and his right hand lacked the tops of two fingers. Gang members had accosted him on the street and wrapped fishing line tightly around them, said Nery, whose last name is withheld to protect his minor cousin.

While the migrants’ stories couldn’t be independently verified, violent gang recruitment and extortion is pervasive in Central America, said Ev Meade, director of the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego. Claiming children or amputating fingers is consistent with a culture of “extreme threats and practices of violence,” he said.

Violence, along with economic motivations, prompts Hondurans to flee to the U.S., Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández said June 13 in Washington, D.C. Since he took office in January, Hernández said, the government has intensified enforcement.

Many children are “fleeing because of the security problem, but we have been moving forward and our program has had some important successes,” he said.

For Carlos, home was scant sanctuary. He said that he left his mother, 12 siblings and an alcoholic father who beat him. He dropped out of school at 13 and, he said, struggles with reading, except for the Bible.

His journey of 1,700 miles (2,700 kilometers) took about a month by bus and foot, and he arrived in Reynosa last week carrying just a sack of a few extra clothes.

“I want to work,” he said, perhaps in construction and carpentry. “Maybe I can bring my family.”

Minors such as Carlos said friends and family tell them they’ll have a better chance to stay permanently in the U.S. if they surrender to border agents. Doing so sets in motion a legal process that can last years.

The children are supposed to be held 72 hours or less in border-station cells, which usually offer only concrete or metal benches and a blanket, Brané said. From there, they go to resettlement shelters or emergency accommodations at military bases or other locations, she said.

They aren’t entitled to legal representation. In the Río Grande Valley, that falls to the Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project, a bar association group that’s grown to 32 lawyers and paralegals focusing on child cases, up from nine in late 2011, said Jackson, its director. A Justice Department program announced June 6 will dedicate 100 more lawyers and paralegals to helping the most vulnerable.

As of June 10, 1,632 detained children were in Río Grande Valley shelters alone.

Marlo, a 15-year-old with a mohawked tuft of hair, presented himself to agents in February. He was released to live with relatives in New Orleans until a judge weighs his case. He has nothing and no one to return to in Honduras, he said as he waited in a windowless room outside a Harlingen, Texas, immigration court, where he came to get his case transferred to his new hometown.

“I came to study here and make a life,” he said.

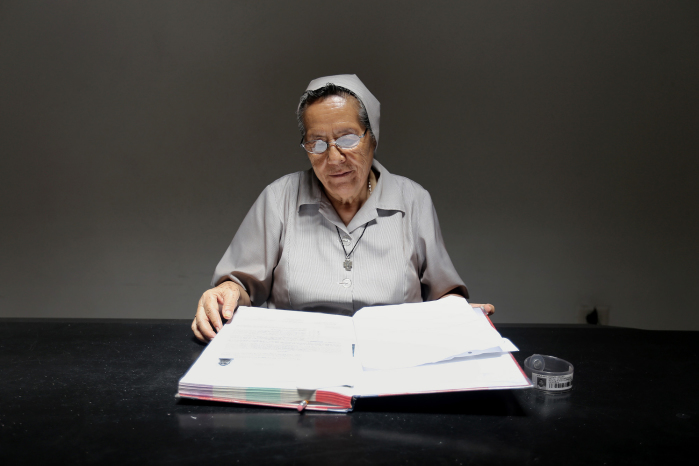

Across the border, Carlos took refuge from the 97 degree heat in the air-conditioned office of Angeles Caballero Gallegos, who helps run Senda de Vida. He sat in a folding plastic chair and gazed at a fresh pair of blue sneakers they’d given him along with a toothbrush. Carlos told her sheepishly that he’d surpassed the official three-day limit.

Hardly anyone stays just three days, she replied. Carlos said he didn’t know when he would tackle the last quarter-mile that stood between him and the United States.

With assistance from Mark Niquette in Columbus, Sandrine Rastello in Washington and Bill Faries in Miami.

© 2014, Bloomberg News