There is one lying there, in the shadows, where the blue pedestrian bridge crosses over the highway. Investigators approach the body while cars continue traveling in both directions along the loop of road known as the Circunvalación, which circles Costa Rica’s capital, San José, eventually passing through this neighborhood, Hatillo, on the southwestern edge of the city.

Red marks on the neck, which clash so visibly with the pale body drained of its last breath, are the first things investigators notice before they lift the naked corpse into a bag.

This lifeless body belongs to a mother. Though she’s been robbed of her voice, she has a story.

She had a name before he left her there dead under the bridge, for anyone to see. She was Tania Marlene Barrientos Astúa. She had four children.

Tania was once a child, too, who bloomed with potential.

As the youngest of nine kids, she had to be strong to survive after her father abandoned the family, leaving a single mom to take care of her and her older brothers and sisters in central Hatillo, a notoriously rough district.

She was the captain of the volleyball and basketball teams at her school. Always an extrovert, Tania was one of the popular girls, going out with friends and getting chased by boys.

But she grew up too quickly. She started going out with the wrong people. And the wrong people are easy to find in a place dominated by drug traffickers and pocked with shacks – known here as “bunkers” – where drugs and sex and violence are traded and distributed with ease.

Falling into a pattern as cyclical as the highway that runs around the city, she started stealing with her new friends in order to pay for crack and cocaine. She sold her body for drugs, too. She would do anything to stay high, even if it meant getting locked up a few times for armed robbery.

Fear has no place in the bunkers, where the need to consume becomes the only engine moving the body. Death looks easy, almost welcome, when compared to life here, where men and women are beaten to death for no more than the shoes on their feet.

Tania, a longtime addict, knew how cheap life could get in Hatillo while she sold herself on the corners. She was last seen by her family on July 20, five days before her body was found under the bridge.

Her older sister Marianela, who helped watch over her when their dad left, took her in and fed her when Tania knocked on her door. Before then, Tania used to come about twice a week, getting hungrier and frailer each time.

“Thank you, sis,” Tania said to Marianela for the last time before she walked back to one of Hatillo’s bunkers. “You know that I love you very much. May God bless you.”

Marianela said the whole family, including the four kids Tania left behind, was shocked when they heard she was dead. Sure, the drugs had made her skinny and unhealthy-looking, but Tania could fight like hell. It didn’t seem like she would ever give in.

When they found her, her mouth was open. She’d been strangled. Semen was found on her body. And the pattern was just like all the others.

Her death was the sixth – but not the last – to be attributed to a serial killer stalking San José’s slums. The killer, who has been dubbed “Mata Indigentes,” or “Killer of the Poor,” is still at-large, targeting impoverished, drug-addicted women like Tania. He is now believed to be the second-most prolific serial killer in Costa Rican history.

And yet, hardly anyone in the city seems to care.

The bunkers

In Alajuelita, just south of where most of the murders have taken place, some semblance of salvation exists. Within the fortress-like barrier surrounding the Christian-based Génesis Foundation, a social services organization, there are women who fit the profile of Tania and the other murder victims.

Any of the former drug addicts who now sit in a semicircle at the foundation’s rehab center could just as easily have been one of them. Eight of them have gathered to talk to a reporter, the same number of victims that the Judicial Investigation Organization (OIJ) officially attributes to the serial killer Mata Indigentes.

Each is a survivor of the bunkers who, like Tania, resorted to prostitution and crime to scrape up enough money for the night’s drug supply, most commonly crack and cocaine. They’ve all heard the same rumors about the killer, of whom word spreads through the neighborhood like a ghost story. But most of the women he’s targeting are too numb to be moved by fatal tales.

“When you are high on those drugs, the last thing you care about is dying,” said one woman who has been in the rehab center for three months. Due to the foundation’s privacy policy, The Tico Times was not permitted to publish the women’s names.

“There’s even times you would prefer to die because there’s no longer a drug strong enough to make you feel good,” another said. “Anxiety starts kicking in. When one substance isn’t enough, neither are a thousand. And that’s the end of it.”

Many who frequent the bunkers have cut ties with family and friends in favor of drugs and fellow users.

“I have gone to the bunkers to drink rubbing alcohol,” one woman said. “I went there because I needed the company of other addicts. I didn’t want to be in a social place like a bar. I wanted to feel isolated in company.”

The isolation surrounding most of the serial killer’s victims has made the killings hard to solve, and easy to forget — at least for those removed from the dark world of drug bunkers and street corners.

Members of the Génesis Foundation go through the bunkers on Fridays to feed addicts and, hopefully, bring some back to the center to get cleaned up. Some of the women who get to Génesis share stories about the killer with the foundation’s cleaning lady, Evelyn Porras Suárez. She says they talk of a rich man who is bent on revenge after he contracted HIV from a prostitute in Hatillo, a place into which outsiders rarely volunteer to go.

But those who live in this world, if they take enough time off drugs, begin to see more and more clearly the terror rolling through the concrete wilderness. If it’s not a serial killer threatening the lives of women like those at the Génesis Foundation, it’s other lingering dangers that follow the sunset – as subtle as disease and as conspicuous as drug gangs.

“When the night comes, there’s sadness,” Porras said, her dark hair flowing over her pink, flower-patterned shirt. Before coming to Génesis, Porras spent 20 years as a drug-addicted prostitute in San José’s Zona Roja, just north of downtown.

When she was living in the streets, Porras remembers the time a violent man picked her up from a corner, paid her for sex, and proceeded to beat her for what felt like the entire night. He almost beat her to death, but he stopped and eventually kicked her out of his car on the side of a highway. Only God knows why she didn’t die that day, she said, or some other day during that life she left behind.

“I know the devil always wanted to destroy me,” she said. “But he didn’t.”

The psychopath

For only a moment, the large metal cross on the mountaintop above the Génesis Foundation breaks through the muddy-colored clouds of an early afternoon rainstorm. It’s La Cruz de Alajuelita, a monument on Cerro de San Miguel, south of San José, once regarded as a host for religious pilgrimages.

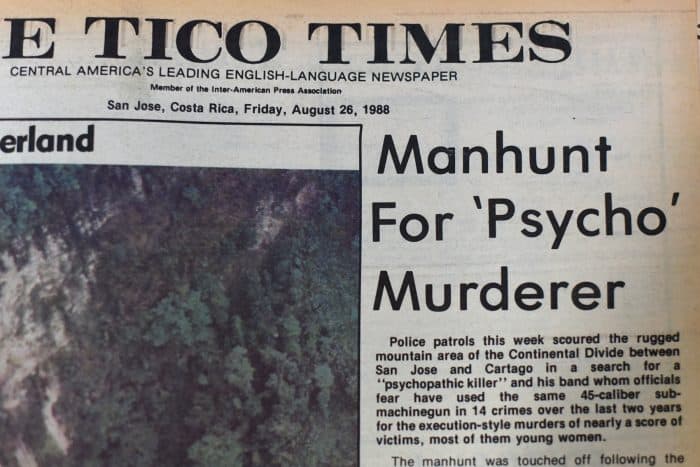

It’s now known as the site of the most infamous murders in Costa Rican history. Seven bodies – six of them little girls – were found by the cross on April 6, 1986, exactly one week after Easter.

Marta Eugenia Zamora had set out on a pilgrimage that afternoon with four of her daughters and two of her nieces to La Cruz. Zamora made the hike to fulfill a promise she made to God after recovering from a chronic disease. While she and the girls rested at the end of the steep trail, a killer later nicknamed El Psicópata, or The Psychopath, murdered them and raped Zamora and two of the older girls.

The victims’ bodies, stained with blood, were stacked next to each other in two rows in a ditch, a style of disposing bodies characteristic of guerrilla warfare.

The youngest victim was 4 years old.

At the time, police said there was no clear motive. A few years later, the Penal Branch of the Supreme Court convicted four men of the crimes. Meanwhile, neighborhoods to the south and east of San José continued to rack up murders, and detectives later connected those murders to the massacre at the cross, and to El Psicópata.

In 1992, a court absolved the men who had been convicted of the Cruz de Alajuelita massacre. But it was already too late for most of them. One was killed in prison. Another was killed in an accident on the highway. The third committed suicide. And the fourth became a reclusive pastor who wouldn’t talk to detectives.

Meanwhile, over the next decade, 12 more bodies accumulated southeast of San José, all located within a triangle marked by Desamparados in the southern part of the Central Valley, Cartago to the east and Curridabat to the north. The area became known as “El Triángulo de la Muerte” – the “Triangle of Death.”

From 1986 to 1995, fear hovered like a constant storm over the women living in that part of the valley.

El Psicópata went after his victims with an M-3 submachine gun and a surgeon’s knife, which he used to cut off nipples and parts of his victims’ vaginas. Criminologists said he probably saved them as trophies.

He also killed couples making love in their cars at Parque La Amistad, a big park east of San José. Most famously, he would only kill after the sun went down and gave way to a full moon – a moon he would try his hardest to turn to blood.

Rumor had it the killer had been abused and abandoned as a child, and that his mother hated him.

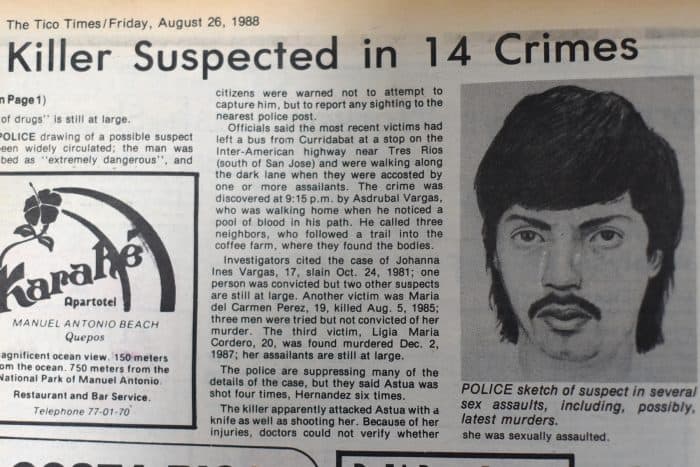

Eventually, OIJ officials laid out a profile of the killer: They thought he was a Nicaraguan Contra soldier because of his precise shot and apparent experience in mountain terrain. They speculated that he was spurred on to kill by his deep hatred for women.

Before El Psicópata killed Ligia Camacho on the night of July 14, 1987, he watched her for a long time through the window of her apartment in San Antonio de Desamaparados. She had the light on and couldn’t see anything in the coffee farm outside, where the killer sat with his gun. He watched as she touched herself in her apartment, the curtains open. She was reading a book on how to reach a better orgasm when he shot her.

According to news reports at the time, the killer then knocked on the door and told Camacho’s parents that he was a policeman, presumably so he could kill them as well and mutilate Camacho’s corpse. They refused to open the door.

After Camacho was killed, marking the fourth crime scene, OIJ began to treat the killings as the connected works of a serial killer.

Three years later, detective and eventual OIJ chief Gerardo Castaing was assigned to the case. It’s one that hasn’t left him since.

Now 65, deep, dark rings swallow the space around the retired chief’s smoke-tinted eyes. He looks as if he’s lived an eternity without sleep as he sits at a McDonald’s in Curridabat on the edge of the Triángulo de la Muerte.

The way he talks of his past, confusing tenses and subjects, makes him sound as if he was there, on the nights that each of the 19 killings were taking place. He speaks as if he were looking through the killer’s eyes.

For Castaing, the murders have become a lifelong obsession. He continues to investigate the crimes even though he’s long retired from the OIJ, and the statute of limitations ran out on the murders a decade ago, making a conviction impossible without any new evidence.

He talks about El Psicópata, and serial killers in general, with a slight air of reverence.

“They have good communication skills and they are usually attractive,” he said. “It’s like they have an angel above them.”

But what separates El Psicópata from other murderers in Costa Rican history is the unparalleled, myth-like fame that sprang from his attacks. Since his chain of murders began on the mountaintop rising over Alajuelita, El Psicópata has grown into the country’s most notorious legend, with a succession of news articles, books, and even a film, all made in his name.

Mention La Cruz de Alajuelita – which, on clear days, is visible from almost any point in the city – to anyone in San José, and they’re likely to think first of El Psicópata and the massacre he’s thought to have committed there.

Now three decades after the horrific crimes, below the cross in Hatillo’s collection of slums, a new type of terror stalks the streets. The city’s latest serial killer, Mata Indigentes, is killing at a faster rate than El Psicópata ever did, and sometimes in even more brutal and violent ways. And yet he emanates from the capital’s most-overlooked neighborhoods as only a whisper. The general public seems barely aware that he exists.

Four monuments to Christ in the hills around the Central Valley mark the points of a giant, invisible cross stretching across the valley. All of the murder sites attributed to El Psicópata and Mata Indigentes lie in the southeast quadrant of this cross.

The mind of a killer

Once, a telephone ring pierced through the silence of Castaing’s empty office while he worked late at night.

“Gerardo Castaing?” asked the voice on the other line.

“Yes?” he said.

“You’re never going to catch me,” the voice said before hanging up the phone.

That voice still echoes through Castaing’s memory, as he continues his obsessive search for El Psicópata. The FBI confirmed that the string of murders was the work of a serial killer a year after the final pair of bodies appeared in Desamparados.

Castaing, now considered one of the country’s foremost criminologists, has spent much of his life trying to put himself in the minds of murderers and rapists. But each time, the psychopath’s almost divine talent for blending in makes finding them nearly impossible. While they hide their rage and appear as model citizens during the day, at night they can wash entire cities with blood.

The standard profile of a psychopath, Castaing says, is a male, 24-40 years old, with a successful job and a deep intellect.

“There’s debate as to whether a psychopath is born or made,” Castaing said. “But it’s simple: A psychopath brings a certain mental disposition, so if they suffer a traumatic experience, it could completely alter their personality.”

Above all, Castaing, says, a profound narcissism runs through the psychopath, who feels that what he’s doing is destiny, leaving him with no remorse when he’s done killing.

“They assign responsibility for the crime to the victim,” Castaing said. “They think they are not the murderers. They put no blame on themselves, instead thinking the victim is the one who made them kill.”

So, when current OIJ officials talk about the Hatillo killings and say they haven’t seen a string of murders as consistent and gruesome since El Psicópata, those paying attention may think that Costa Rica’s most famous killer has been resurrected.

Castaing said journalists ask him all the time if the murders in Hatillo could be the final work of El Psicópata.

“It could be a serial killer, but it’s not El Psicópata,” Castaing said. “They may both share the label ‘psychopath,’ but they don’t share the same identity.”

Castaing battled with fellow OIJ officials and city police for a long time, not just over who committed the crimes, but how many people committed them. The former chief, who started as a 19-year-old police officer before rising up the ranks of OIJ, long said that evidence from at least three of the crime scenes pointed toward multiple men working together.

Plus, a witness – the only known witness to one of the serial killer or killers’ crimes — said she saw several men apparently involved in one of the double murders attributed to El Psicópata.

The witness was a young woman who was walking at night on a street bordering a coffee plantation in San Vincente de Tres Ríos minutes after Victor Hernández and Aracelly Astúa were murdered on Aug. 21, 1988. Under the light of the full moon, she could see three men among the coffee bushes. She later told Castaing and OIJ detectives that the men called out to her and told her to come onto the plantation. Just then, a car drove by and turned around, scaring them off. The woman went to get her husband, an evangelical pastor in the neighborhood, who walked with her back to the coffee field. There they discovered a trail of blood, which turned out to be from Astúa’s body.

In 2002, OIJ officially took the stance that the Costa Rica serial killer acted in tandem in at least a few of his murders. But that’s as far as the case went before the statute of limitations froze any legal action authorities could potentially take. After the four men were absolved of committing the massacre at La Cruz de Alajuelita, no one else has ever been brought to justice for the crimes attributed to El Psicópata.

Now, as another killer sweeps through the worst parts of the city and touches the most marginalized people with death’s fingers, detectives are grasping for leads as to who he is. A revolving door of suspects has been detained and then let go after DNA tests failed to match them with the fluids and hairs left on the bodies.

Police went into the bunkers in August and arrested a 30-year-old man from Curridabat after they said they received tips from area prostitutes that the man had contracted HIV and was the one responsible for the killings. Weeks later, after a DNA test came up negative, OIJ officials crossed him off as a suspect.

The search for a psychopath is made even harder considering the victims he targets. Each one of the women he’s killed has spent considerable time on the streets and away from her family. Those who knew the victims and were familiar with their daily lives leading up to their murders are almost invariably drug addicts or convicted criminals.

OIJ homicide director Hugo Monge told The Tico Times that the killer frequents the area, getting to know the victims and gaining their trust before murdering them. Monge said in addition to having DNA samples confirming that fluids found on three of the victims are from the same person, detectives also have security camera footage of the killer walking away from one of the murders, although they have yet to release the footage to the public or the media.

Monge’s co-worker, OIJ Assistant Director Luis Ávila, said it’s likely the killer has psychopathic tendencies and is motivated by a sinister revenge plot.

“It could be a person who is feeling contempt for life, particularly towards these type of women,” he said.

The women who have lived in the bunkers believe the killer is a man from an upper-class part of the city who works a lucrative job, possibly as a banker, and comes to the area to buy drugs and sex. They think that when he contracted HIV from one of the district’s women, he set out to massacre the area’s drug-addicted prostitutes.

Castaing agrees that the man tearing through Hatillo is probably from a separate, more affluent part of the city.

If the killer was from the neighborhood, “they’d get him,” Castaing said of his successors at OIJ. “We have so many informants there. When no evidence appears, you know he’s not from that socioeconomic class.”

Castaing and other investigators admit that catching a serial killer almost always happens by coincidence, or some uncharacteristic slip-up by the subject. In the United States, it was a routine traffic stop that ultimately led to the conviction of Ted Bundy, who killed more than 30 young women over two decades. Like the psychopaths that Castaing describes, Bundy was known to gain women’s trust with his handsome looks and charisma, but under his outward demeanor, as Bundy would later tell a biographer, he was fueled by a lifelong hatred for his mother.

In the Mata Indigentes case, investigators need to figure out what motivates the killer, Castaing said. “Everything in life is generated by motivation.”

The nameless

A cry bellows over the tin-roofed slums before darkness devours the sound.

A man walks through the night, faceless and silent. Behind him, in an abandoned lot in Hatillo’s eastern neighbor of San Sebastián, is the first body. It’s that of 30-year-old Natalia Felicia Salazar. She was a few months pregnant, those who knew her say, when she was killed in early April.

Neighbors later said that they heard a woman screaming, “No, mi amor. No, mi amor!” a few nights before Natalia’s body was found, on April 10, decomposing under the foliage in the lot.

Natalia had recently spent four months at the Génesis Foundation in Alajuelita, trying to get clean for her 14-year-old daughter and the child to come. But she was eventually kicked out for not following foundation guidelines. She relapsed into drugs.

After Natalia was killed, German Gómez, the director of Génesis, said he took the woman’s teenage daughter into the bunkers to try to sway her from following the same path. They went to La Reina, one of the city’s most dangerous slums, where they saw women high on crack and heroin lying vapid in the grotesque corners of bunkers. When the tour finished, the teenager was in a state of shock, Gómez said.

But there are few crossroads here in Hatillo’s bunkers, few options for the children, like Natalia’s, of broken homes, caught in a proliferation of drug-spurred violence. Not far away is the affluent southwestern San José suburb of Escazú, where private schools and malls give it the feel of another planet.

One less addict. One less prostitute. One less thief.

It doesn’t take long to count the reasons why so many people in the city either aren’t aware, or just don’t care, that an at-large killer has strangled the life out of eight women.

Some attention has come to the murders through news reports in the Spanish-language tabloid Diario Extra and television channel Repretel, which have cast a bit of light over an area of the city shrouded in obscurity.

But Mata Indigentes has killed under a spell of relative silence compared to El Psicópata’s infamy.

Alejandra Mora Mora, the president of the National Institute for Women, said in September that the murders of these impoverished women should be considered a national emergency.

“Many people judge these women for their lifestyle, even those who are already dead, forgetting the story behind each one of them that made them vulnerable in the first place,” Mora said in a statement. Mora suggested that Costa Rican society considers the women dispensable.

“We shouldn’t allow these deaths to be met with indifference,” she said.

In this case, one less drug addict on the streets is also one more motherless child who gets raised in the same type of broken homes that define most of the victims’ pasts.

El Psicópata left a bullet mark over the lips of some of his female victims, which Castaing said was to symbolize that they could no longer speak. It was a way of showing those who came upon the body that she would never again have a voice to reveal the details of her fate.

Mata Indigentes’ pattern of strangling his victims suggests a similar message. It ensures that women who already exist on the periphery of a society remain unseen and unheard.

Both serial killers also raped their victims.

“For serial killers, rape isn’t an end,” Castaing said. “It’s a means to satisfy not sexual needs, but psychological ones. Revenge. Fury. Power. Assurance. There’s a series of reasons why they rape and kill.”

On Sept. 7, two boys were looking through trash by a dirty, urban river when they found the body of Franciny Bermúdez Romero, decomposing right by San José’s Children’s Museum. She was completely naked, except for the shirt the killer had thrown over her face. He strangled her to death and left her there in an abandoned lot, like the others.

But unlike the others, Franciny was the first suspected victim of Mata Indigentes whose body was found north of the city, showing that the killings could be leaking out of Hatillo and into other parts of San José.

She was 18.

Franciny’s was the eighth body found in six months, tallying a horrific, plague-like rate that’s never been recorded before in the country, not even at the height of El Psicópata’s reign of terror. Ávila and current OIJ investigators call the killings a “phenomenon,” while the women who’ve escaped the bunkers call it a purge.

How many more women will be permanently wiped off of street corners and swept out of bunkers before authorities find the killer? Or will he remain as elusive as El Psicópata?

It’s not easy to find a killer where no one wants to go, where a man hides under more than just the night. Mata Indigentes is a nickname without an identity, and a trail of evidence without an answer. He’s a psychopath, and he could be anyone.

“The thing about a psychopath,” Castaing said, “the problematic part of this investigation, is that we all have psychopathic features. You and I and everybody has them.”

—

Editor’s note: OIJ spokesman Marco Monge said Friday that police have identified a suspect who they’ve connected through scientific evidence to three of the recent killings. He said authorities are still trying to determine whether the suspect is connected to any other murders. We will continue to update this story as more information becomes available.

Melissa Sánchez contributed to this report.