The proposed construction of a landfill in the canton of Mora, 20 kilometers west of San José, has angered local residents who say they will fight to protect their natural resources. While Mora is located in San José province, residents from both Alajuela and Puntarenas provinces also have joined the battle. But time seems to be running out.

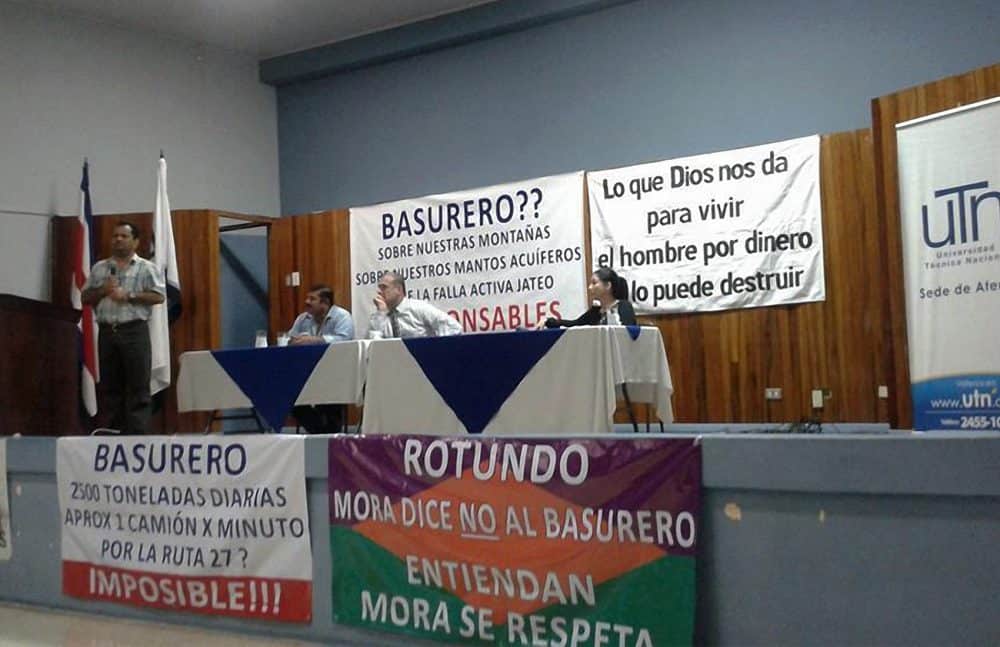

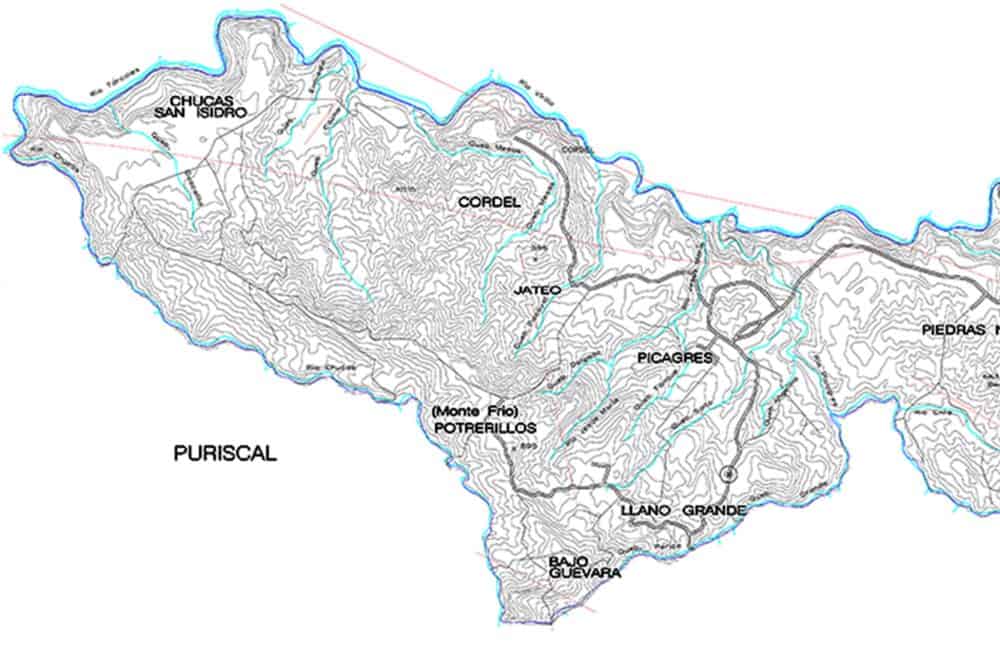

The most vocal opposition comes from the Mora Civic Defense Committee, a citizen advocacy group supported by the local municipality. Committee members say the site chosen for the landfill, in Jateo de Mora, is located in an area of aquifers and rivers that supply fresh water to several communities west of the Central Valley.

The project would be built on part of a 238-hectare property located near a geological fault, and “a moderate earthquake could cause waste to leak into those aquifers, polluting water for thousands of homes,” Eladio Campos, one of the group’s leaders, said.

The landfill proposal was presented by private contractor Parque Industrial Jateo in 2004. At the time, the company said it was the most suitable option to replace landfills in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), an urban area in and around San José that includes 60 percent of Costa Rica’s population. Specifically, it would help address a lagging problem with waste management following the 2007 closing of the Río Azul landfill in La Unión, Cartago, which for 34 years received 750 tons of garbage a day from 11 GAM cantons.

After Río Azul closed, municipalities began sending garbage to smaller landfills in San José, Alajuela and Cartago provinces.

The current project has been approved by Costa Rica’s Environment Ministry (MINAE), MINAE’s Environmental Technical Secretariat (SETENA), the Health Ministry and the Federated Association of Engineers and Architects. It still needs approval from the Mora Municipality, Parque Industrial Jateo attorney Alberto González Carmona told The Tico Times.

González said that in addition to obtaining a municipal construction permit, the company must fix an access road to the property. He said work on the landfill likely will begin in eight months. The project would have the capacity to receive some 2,000 tons of solid waste a day, but the company has stated that it would not exceed 1,500 daily tons of garbage.

Since 2005, Mora municipal officials have denied the company construction permits in what marked the beginning of an ongoing dispute that now includes citizens and officials from three provinces. Throughout the process complaints over the landfill have been filed with the Ombudsman’s Office, the Environment Ministry and the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, or Sala IV.

Taking on Goliath

Following SETENA’s approval in 2010, municipal officials responded by denying construction permits at least three times, Mora Mayor Gilberto Monge Pizarro said.

“SETENA approved the project’s environmental feasibility study despite several complaints and appeals filed by Mora’s citizens and municipal officials,” the mayor said.

Those appeals argued that there are no mitigation plans for the expected heavy traffic of garbage trucks, the lack of proper roads to the landfill’s proposed location, the risk of polluting local aquifers and the negative effects on protected areas in Mora, according to Monge.

But MINAE, SETENA and the Sala IV dismissed all of those appeals, including the last one filed by the mayor, which was rejected on July 29, 2015.

Monge criticized MINAE for approving the landfill instead of seeking more “efficient” and “environmentally friendly” solutions.

“MINAE decided on a mega-landfill over several proposals that included bids to develop gasification projects, which would have provided clean energy,” he claimed. However, gasification proposals have generated both controversy and opposition in Costa Rica from critics who say it is not an environmentally viable option.

The mayor, who was re-elected last Sunday for another four-year term with the New Generation Party, said he fears the social, economic and environmental problems that other communities with landfills in their backyards have faced.

The operation of landfills in Costa Rica, Monge said, “traditionally has been linked to the proliferation of slums, trash sifters and pests.”

He also noted that current landfill regulations do not establish any requirements for recycling. Therefore, “among all available options, [a landfill] is the one that generates the most solid waste,” he said.

The garbage highway

Eladio Campos, the leader of the Mora Civic Defense Committee, said that in addition to water contamination risks and environmental damage, the project’s approval was granted by MINAE without considering other factors. Campos noted that there is no paved road to the project’s location, a mountainous area whose only access is along steep slopes.

“We find it hard to believe that trucks loaded with tons of garbage can make it to the site, traveling along a narrow gravel road,” he said.

The company says construction of an adequate access road is planned in the short term. “We are aware that a better road is required to allow the passage of our trucks,” attorney González said.

Monge said trucks would travel along a stretch of Route 27, the main highway connecting the capital to the Pacific province of Puntarenas, in an area currently booming with high-profile commercial, residential and tourist developments.

Route 27 also is the main highway for cargo transport between Pacific ports and the GAM, and garbage trucks would increase the traffic of heavy vehicles. Monge estimated that the amount of waste would require trucks to be accessing and traveling on Route 27 an average of every 10 minutes.

González countered that the highway is the best and only option to access the area.

“I wish the country had more roads, a bigger highway with more lanes, but Route 27 is what the country has, and we will use it,” he said.

Landfill plans do not outline alternate routes, and a closure of Route 27 – prompted, for example, by landslides during the rainy season – could force a large number of trucks to travel through Mora communities, Monge warned. That would take them through El Rodeo, a 400-hectare biological reserve that protects the only premontane primary rain forest in Central America and the only protected area west of the GAM.

A study by experts from the National University’s School of Geographical Sciences states that the road between Ciudad Colón and the University for Peace (UPAZ) at El Rodeo “is not suitable for continuous transit of heavy vehicles.” It also says that passage of vehicles carrying garbage “could have a negative impact on El Rodeo biological reserve’s environment.”

UPAZ officials also filed a complaint with the Sala IV to prevent the construction of a road through El Rodeo, but it was dismissed.

El Rodeo natural reserve is located within the Virilla River basin and forms a biological corridor connecting the river basins of Pacacua, Quebrada Honda, Jaris and Picagres. This corridor forms a natural link of flora and fauna along the southwest region of the Central Valley, according to National University researchers.

UNA biologist Luis Fournier Origgi filed another complaint arguing that expanding the road through El Rodeo to allow garbage trucks would cause serious damage to the natural reserve.

“The expanded road would result in a dry canal that might interfere with the free circulation of groundwater and which also constitutes a major obstacle for the free passage of wildlife in that area,” Fournier noted. He said more than 50 species of mammals and 150 bird species could be endangered, as well as dozens of amphibians and reptiles, some of them already listed as endangered.

González said Route 27 would not be a problem because most of the landslides occur several kilometers down the road, “usually from Atenas on.”

“The entrance to the project is several kilometers before Atenas,” he said.

Closures on Route 27 “usually are brief because government officials respond quickly to reopen the road when they occur,” he added, noting that if a landslide closed the highway the company would use any alternate route available.

“Waste collection and disposal is something we can’t just stop, and the country can’t afford to keep Route 27 closed for an extended period,” he said.

In its approval report, SETENA stated that the company’s plan “has responded satisfactorily to all concerns raised by Mayor Monge and the citizen groups.”

González said the company’s plan in the past 15 years has been analyzed and approved by over 30 professionals from all government agencies required by law, and that only the Mora Municipality is blocking it. He said that within a month the company would again submit a construction permit request to the municipality.

Regarding the risk of contamination posed by leaks through geological faults, SETENA accepted the company’s technical plans and the argument that country regulations state that the existence of a fault in a highly seismic country like Costa Rica is not a reason to prevent the construction of a project.

“Companies, under current regulations, only are required to maintain a minimum distance —60 meters— from any fault,” González said.

The company submitted to SETENA an official document from MINAE’s National System of Conservation Areas stating that the property where the landfill would be built is not located in an official biological corridor or within any areas of physical or socio-economic impact.

“We are aware that nobody wants to live near a landfill. We all produce trash, but no one wants to deal with it. Costa Rica has a big problem with waste disposal and we’re offering a solution,” González said.

Risk assessment

The website of the National Emergency Commission (CNE) has an overview on natural hazards in the canton of Mora that states that a moderate to strong earthquake (5 or more degrees) close to the surface “could cause cracking in the ground in the nearby areas of Ciudad Colón, Piedras Negras and Cordel.” It adds that “the soil type present in the area also would favor this kind of process.”

The CNE assessment warns that the area is prone to landslides due to steep slopes and the type of rocks, and a landslide could be prompted by seismic events or heavy rains. It also lists a number of recommendations due to the presence of nearby geological faults and the site’s topographic conditions. Among them, the CNE recommends “avoiding the granting of construction permits in areas near geological faults” and “regulating the granting of permissions in areas prone to natural disasters when approving plans or projects of local importance (landfills, aqueducts, public roads, etc.).”

Another section recommends “promoting environmental education programs to prevent pollution of rivers by solid waste,” something the Mora citizens group says is within the possible risk scenarios in the area, as there has been important seismic activity in the past.

On Dec. 22, 1990, a magnitude-5.8 earthquake with an epicenter located in the adjacent canton of Puriscal affected nearly 500 homes in Puriscal and Mora, according to a report from the University of Costa Rica’s National Seismological Network (RSN). From May 7-31 that same year, the RSN reported a total of 2,024 temblors in the area – 100 of which registered magnitudes between 4.5 and 4.75.

González said that those geological and technical specifications were considered during the planning stage, and the approval of all involved agencies is proof that the company did its job.

New airport?

Residents of the Alajuela canton of Orotina, 60 km west of Costa Rica’s capital, also are concerned about the landfill because they believe it will affect government plans to build a new mega-airport in Orotina. If the project moves forward, the airport would become Costa Rica’s largest air terminal.

Civil Aviation Administration Director Enio Cubillo Araya told The Tico Times that technical studies for the construction of the new airport are currently on their way, and results are expected in a year and a half.

In a written response, Mauricio Espinoza, who coordinates civil aviation’s projects commission, told members of the Mora Defense Committee last December that the commission is “working with an international group to define the final location of the airport.”

Espinoza said he was unaware of the proposed landfill in Mora, but noted that civil aviation in the past has analyzed possible security risks by landfills located near airports.

“Unlike an open dump, landfills operate under very acceptable conditions,” Espinoza said, citing the La Carpio landfill west of San José. La Carpio is located in an area between the Juan Santamaría and Tobías Bolaños international airports.

“In principle we don’t see any situation that would affect the project, considering that waste disposal procedures include highly effective control of birds and other risks,” Espinoza said.

Opposition to the landfill now includes residents from adjacent cantons such as Puriscal (San José province), Atenas and Orotina (Alajuela province), and groups in Puntarenas province.

“We’ve met with community leaders from all of those areas, and they agree the mega-landfill would have a negative impact on their economies, their social development and especially the environment,” Campos said.

Residents and municipal officials from these communities periodically hold town hall meetings to discuss actions to block the landfill. In Mora, both Mayor Monge and Campos said they will keep fighting, against the odds.