YAWEPARE, Ecuador – An oil pipeline runs through this village to a Chinese rig at the end of the road. At night, when the rig is pumping, the pipeline is too hot to touch, but villagers say that in the morning it’s a good place to dry laundry.

That is its only apparent benefit to the families here, members of the Waorani tribe, lured out of the jungle by missionaries more than a generation ago. Its members live in plank-board shacks with no running water, amid the noise and dust of the fuel trucks, road crews and oil workers.

“All of this used to be our territory,” said Venancio Nihua, the son of a Waorani hunter, trying to support his seven children by raising chickens. “We don’t want the oil companies to come any farther.”

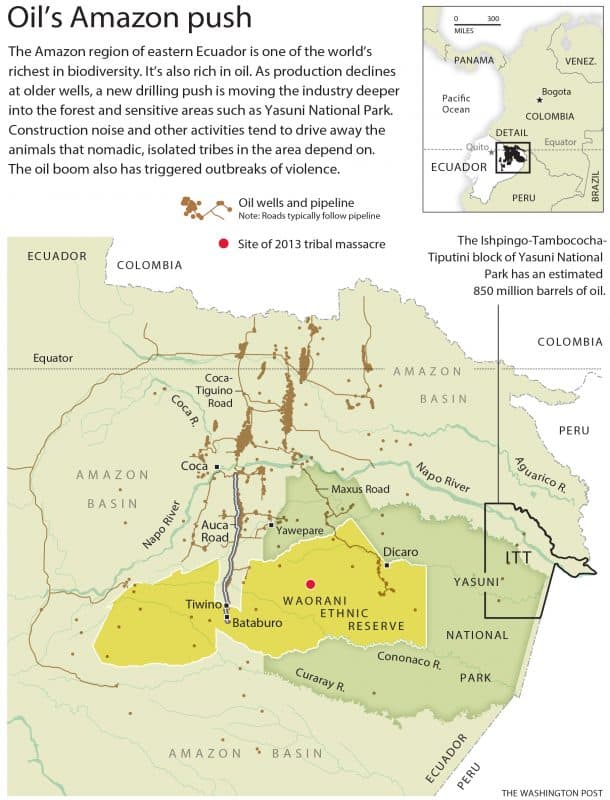

An unprecedented drilling push by Ecuador’s government has brought new tensions to Yawepare and the country’s Amazon lowlands. As the chain saws and bulldozers cut deeper into the forest, critics say the government is triggering brutal warfare between the Waorani and a smaller, breakaway tribe living in “voluntary isolation” beyond the oil frontier.

Ecuador, an OPEC member, pumps more than 500,000 barrels of crude a day, but with production falling, the country is moving to drill inside one of the world’s most ecologically complex and fragile places, Yasuni National Park, an area that is also home to the tribes. The government says it needs the money to pull the country out of poverty and provide education, housing and electricity to the Waorani and other forest inhabitants who have been living on the sidelines of the oil rush for too long.

The families of Yawepare say they would like those things. If the Taromenane don’t come to attack them first.

“They are watching us right now,” said Nihua, who, like others here, views the reclusive Taromenane with a mix of reverence and fear. “They drink ayahuasca and can see everything,” he said, referring to a hallucinogenic brew.

Last year, after a Waorani elder from another village, Ompore Omeway, and one of his wives, Buganey, were slain, allegedly by the Taromenane, a Waorani war party plunged into the forest to retaliate. Armed with shotguns and rifles, they hunted the Taromenane for a week, found a communal lodge and massacred about 20 people, mostly women and children. It was a devastating toll on a tribe thought to have only 150 to 300 members, ostensibly under the strict protection of the Ecuadoran government.

Two Taromenane girls who survived the attack, ages 6 and 3, were taken to the Waorani village. It was only after word of the massacre began to leak out that Ecuadoran authorities intervened, sending soldiers in helicopters. They removed the eldest girl, but the abductors have refused to release her sister.

Seven Waorani were arrested, and the videos they made of their attack are now evidence against them. Yet the origins of the violence are disputed. Fellow villagers say the Waorani don’t belong in jail, arguing that they can’t comprehend Ecuadoran law and that their actions were a traditional form of justice.

Deadly raids on rival clans, and on oil workers, loggers and other cowori (outsiders), have a long history here.

But the scale of the massacre, and its timing, are inflaming the fight over the government’s oil push. Environmentalists and indigenous advocates say the Taromenane attacked Omeway because he failed to satisfy an impossible demand: that the oil workers stop encroaching into the nomadic tribe’s territory.

In a video interview recorded nearly a year before his death, Omeway excitedly tells fellow Waorani the story of his unusual and tense encounter in the forest with Taromenane warriors. They warn him: Tell the outsiders to stay away.

They also ask for a rifle in exchange for one of their spears. Defenders of Ecuador’s oil plans say the video suggests that Omeway could have been slain in retaliation for a bad trade, or for failing to provide the tools the Taromenane demanded.

“We aren’t afraid of anything,” the Taromenane told him, Omeway says in the video. “We’ll come back to visit you, and if you have any problems with the cowori, we’ll help you kill them.”

Within a year of the encounter, he and his wife were ambushed along a trail near their village and struck by Taromenane spears.

The pipeline running through Yawepare feeds a vast suction system that spider-webs through Ecuador’s Amazon region, linking wellheads to pumping stations to storage tanks as tall as the tree canopy. The country has South America’s third-largest reserves, after Venezuela and Brazil, and the United States has long been Ecuador’s biggest buyer. But nearly all of Ecuador’s future exports will go to China to service the country’s growing debt to Beijing.

Some of the most intensive extraction takes place along the Auca Road, in the heart of what was formerly Waorani territory. Its name, Auca, is the word once used to identify the tribe, meaning “savage” in the Quechua language of the Incas.

The U.S. oil company Texaco arrived there in the 1970s, after the Ecuadoran government encouraged U.S. missionaries to help pacify the Waorani. The period coincided with a time of intense violence among Waorani clans, and many families were relieved to escape the killing and gain protection.

Other Wao-speaking clans such as the Taromenane remained in the forest, violently resisting outside attempts to “civilize” them.

The oil and chemical spills of the Texaco era – and claims of exorbitant cancer rates as a result – led to a massive lawsuit by Ecuadoran tribes against Chevron, which acquired Texaco long after the company left Ecuador.

Ecuadoran courts rendered an $18 billion judgment against Chevron in 2011, but the company has rejected the ruling, and Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa has had little success pressuring Chevron to pay.

The damage to the Amazon and its tribal communities became a driving force behind the Yasuni ITT Initiative, a widely publicized proposal floated by Correa at the U.N. General Assembly in 2007.

If international donors would give the Ecuadoran government $3.6 billion, equivalent to half the estimated worth of the oil beneath an especially pristine section of Yasuni National Park known as the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini block, the government would leave the crude in the ground.

Otherwise Ecuador would drill. Critics likened it to a ransom on the rain forest.

The gambit failed, badly. After six years, having raised barely $100 million in pledges and donations, Correa declared that it was time for “Plan B.”

After Correa won a third term in March 2013, the country’s National Assembly – under control of the president’s party – voted to drill the ITT. The government redrew its maps of tribal territory, claiming that the Taromenane and smaller Tagaeri clans didn’t live in the oil-rich areas after all.

Ecuadoran officials say it was the international community that failed to act. “The world’s biggest polluting countries had only rhetoric to offer,” Lorena Tapio, Ecuador’s environmental minister, said in an interview, asserting that new drilling in Yasuni National Park “will not mean its destruction.”

Seismic studies, which typically involve the use of dynamite, are underway, and the government has begun soliciting bids on other petroleum blocks beyond the ITT.

“Every activity generates an impact, but we are going to ensure that the impact is minimal and that the extraction is held to the highest standards, with the best systems of monitoring, enforcement and control,” Tapio said.

The government will deploy surveillance drones, she said, to ensure strict environmental compliance by Petro Amazonas, its state-run oil company.

Augusto Tandazo, an energy consultant in Quito, the capital, notes that Ecuador’s government is constitutionally obligated to develop its oil resources, and although parts of the Yasuni park belong to the tribes, they do not own the oil beneath it.

He laid out the case for drilling in rapid-fire fashion: Ecuador’s energy consumption has nearly doubled in the past decade. The country needs to grow and invest in infrastructure, education and job creation to benefit its 14 million people. Ecuador’s economy is heavily oil-dependent, and without the ITT, production falls and takes Ecuador down with it.

No government would be foolish enough to allow such a thing, Tandazo said.

“These environmentalists and anthropologists want to keep the tribes living in the Neolithic age, naked in the forest, like some sort of tourist postcard,” he said. “It’s clear that they need our help. They want tools. They want contact.”

Nihua’s children do homework by the light of a kerosene torch. Insects swarm through the gaps in the walls, which are bare except for multiplication tables written on the wood in black marker.

Tepa Quimontari, his mother-in-law, sits on the floor, her swollen arm in a sling. She grew up in the forest, speaks no Spanish, and is one of the few Waorani who still go mostly without clothes, wearing only a pair of tattered sweatpants. She says she is the aunt of the Taromenane girls who were kidnapped after the massacre, in which her sister was killed.

In October, she dressed in warm clothing to travel with women from other forest tribes into the Andes on a march to Quito, demanding a meeting with Correa to protest the government’s drilling plans. “I rode in an elevator,” she said.

Correa did not meet with the women.

Quimontari wanted to warn him that if the companies take out more oil, the forest will sink. “There won’t be any animals. The rivers will die,” she said. “More diseases will come.”

With the pain in her hand worsening, Quimontari traveled the next day to a larger Waorani settlement, Bataburo, to see a Waorani “curandero” (medicine man), Bai Ima. She found him sitting in a ramshackle hut beside the empty new home the Ecuadoran government had given him a few weeks earlier, part of its pledge to invest more oil revenue in tribal villages.

Ima said he stays in the house at night but prefers his dirt-floor shack during the day. As he spoke, a fire smoldered and a bright woodpecker perched beside him, tied to a stick. “It’s too big,” Ima said of the three-bedroom, brightly painted home. “Many families can sleep inside.”

The curandero pulled out a smooth, dark stone, examining Quimontari’s distended fingers, and told the old woman not to eat any fish or birds. He spit on the stone, rubbed it, then held it to his ear like a cellphone, saying he would consult other curanderos deeper in the forest.

“Don’t take any pills, either,” he said.

Dozens more gleaming, modern homes and a new school have been built by the government in Tiwano, another Waorani settlement nearby. But community president Ique Ima said the village is not satisfied.

“Not until they pave the streets and build us parks,” he said.

The Waorani know the government doesn’t want any more protests blocking oil workers from access to the wells. But they sense the government is easy prey now, and if anything, they have learned to apply the hunter-gatherer mind-set to modern oil politics, and get as much as they can.

The families in Yawepare were promised new houses too, but they are still waiting.

In the meantime, Nihua’s father, Okata, built a traditional lodge of palm fronds in a clearing behind his house. He says the Taromenane have spent the night there, leaving before dawn. He wants the Waorani to live beside them in peace.

Asked if he regretted giving up a life in the forest as a younger man, Okata said he did not. The animals he hunts have retreated deeper into the jungle, fleeing the noise. But he now takes a rifle and a dog along with his blow gun and poison darts, returning with deer meat and a sack of birds. “When I go hunting, it is the same,” he said. “I remember all the trails.”

Dressed in running shorts and a T-shirt, he rested in a woven hammock after a night of little sleep. Even after walking for a day into the forest, he said, he could still hear the generators from the oil rigs.

© 2014, The Washington Post