Costa Rica’s Santa Elena Peninsula in the northwestern province of Guanacaste was the site of a smoking gun in the 1980s Iran-Contra affair, the scandal that rocked the administration of former U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Santa Elena also was the site of extensive drug trafficking back then, according to pilot who now says he trafficked cocaine and guns to a secret airstrip on the peninsula.

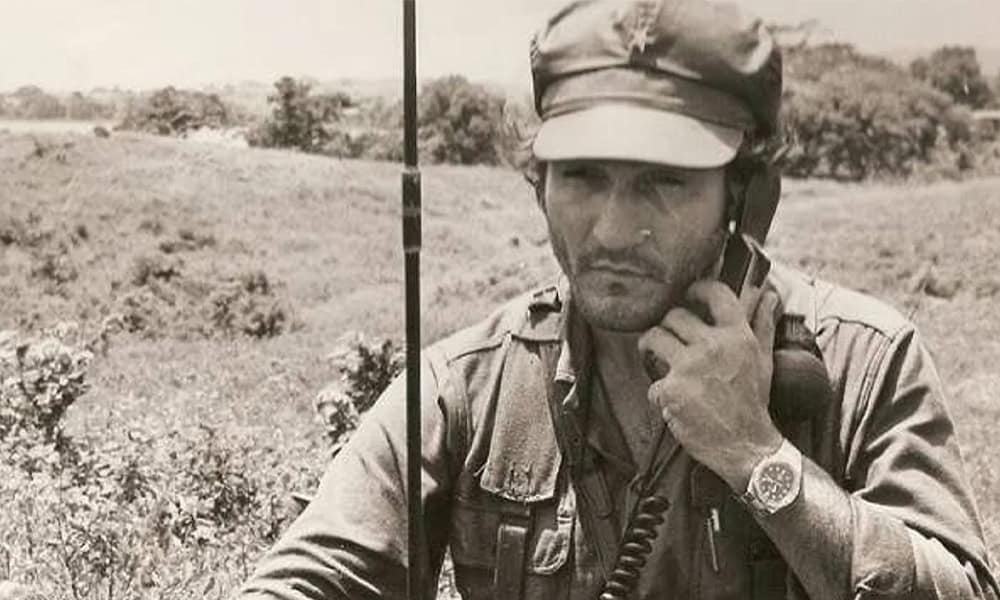

The airstrip was located in Potrero Grande, a 1.6-kilometer valley on the coast some 15 km south of the Nicaraguan border. According to former CIA contract pilot Robert “Tosh” Plumlee, drug smugglers used the airstrip for years, even before U.S. Lt. Col. Oliver North came looking for a staging area for arms flights into Nicaragua’s “Southern Front.”

A team of journalists, including Tico Times reporters, discovered the airstrip in September 1986. “Santa Elena had been on a drug-running route long before we started using it to help arm the Southern Front,” Plumlee told The Tico Times.

Somehow, North fell in with the owner of the property, the Santa Elena Development Corporation, represented by North Carolina native Joe Hamilton. North took out a $5 million mortgage on the property for an unknown purpose.

“Men with maps” approached former Costa Rican President Luis Alberto Monge to obtain his blessing to create a full-scale air base at Potrero Grande, arguing that it would be needed if Sandinistas attacked Costa Rica. After he left office, Monge told The Tico Times he assumed the men were U.S. officials. He readily agreed.

A phantom Panamanian company, Udall Resources, set up by retired U.S. Gen. Richard Secord and “owned” by a “Robert Olmstead” – the pseudonym of William Haskell, a Maryland accountant and North’s Vietnam buddy – was contracted to extend the airstrip in 1984 to enable it to accommodate large C-130 transport aircraft.

Iran-Contra investigators discovered that a “cabal” had elaborated a plan to conceal the backing of Nicaraguan Contras by the U.S. government at a time when the U.S. Congress had prohibited the Reagan Administration from aiding the Contras.

Plumlee said he flew to the Potrero Grande airstrip before North dubbed it “Point West,” beginning in 1983, in a smaller C-123 transport plane. Plumlee estimated that he trafficked up to 30,000 kilograms of cocaine from Medellín and Bogotá, Colombia, out of Potrero Grande.

When Óscar Arias became president of Costa Rica in May 1986, he ordered U.S. Ambassador Lewis Tambs to shut down the site. But the refurbished airstrip had become operational the same month Arias took office, and remained open for business, Plumlee said.

Residents in the neighboring communities of Liberia and La Cruz spotted airplanes flying low over the hills of Santa Rosa National Park, which bordered the airstrip.

A team of journalists set out to find the airstrip in September 1986. When they traveled to Santa Rosa National Park to ask about the mysterious flights, a U.S. scientist working in the park said, “It’s about time.”

If the U.S. government was running a drug interdiction operation through Potrero Grande, it was a secret to the Costa Rican government. After journalists discovered the airstrip, then-Public Security Minister Hernán Garrón said Costa Rican police had seized the airstrip the previous month.

“We didn’t know if we’d find Contras or armed drug traffickers,” Garrón told The Tico Times at the time.

In October 1986, the Sandinista army shot down a C-130 carrying arms to the Contras and captured a cargo kicker named Eugene Hasenfus, the only crew member with a parachute.

Journalists given access to documents found aboard Hasenfus’ airplane linked the flight to the CIA. A Tico Times reporter determined that two phone numbers found in logs in the wreckage belonged to the home and the embassy office of CIA San José station chief Joe Fernández (code-named Tomás Castillo), a foreshadowing of the Iran-Contra scandal that erupted the following November, when U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese revealed that the U.S. government had sold weapons to Iran and used the proceeds to help arm the Contra rebels.

The chain of events raised questions over how much the U.S. government, in general, and the CIA, in particular, had aided the Contra cause when a congressional prohibition was in place.

In Costa Rica, a Legislative Assembly commission, acting on findings richly informed by the U.S. Senate Committee investigating Contra involvement in drugs and chaired by then-Senator – now-Secretary of State – John Kerry, prohibited a number of former U.S. officials – including North and Ambassador Tambs – from entering Costa Rica.

Eventually, the Arias administration expropriated the Potrero Grande land and it became a part of Santa Rosa National Park – but not before a protracted court battle with the airstrip owners and the direct intervention of then-U.S. President George H.W. Bush, who held up an Inter-American Development Bank loan to Costa Rica to prod the Arias administration over the “investment issue.”

The Costa Rican government ended up paying about $13 million for the property, after negotiations arbitrated by the World Bank.

The fact that Mexican drug cartel kingpin Rafael Caro Quintero was a supporter of the U.S.-backed Nicaraguan rebels, providing a training and staging area for arms flights to the Contras at his Veracruz, Mexico, ranch, also casts a different light on the drug lord’s escape to Costa Rica and the circumstances surrounding his short stay in the country.

In early March 1985, tipped off that Caro Quintero was about to fly out of Guadalajara to escape the manhunt that had prompted U.S. President Ronald Reagan to close the U.S. border with Mexico, DEA agents raced to the city’s airport to find agents from Mexico’s Federal Security Directorate (DFS) protecting Caro Quintero’s Gulf Stream jet.

According toHéctor Berrellez, the DEA’s lead investigator into agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena’s 1985 kidnapping, torture and murder, Caro Quintero appeared in the doorway of the airplane holding a bottle of champagne and shouting to the outgunned DEA agents: “My children, next time bring more guns.”

Caro Quintero was flown north to Sonora by Costa Rican pilot Warner Lotz – another CIA contract employee, according to Plumlee – to see his brother Miguel before Lotz flew the cartel boss to his ranch in Veracruz. Plumlee said he was waiting there to take Caro Quintero across the border to Guatemala, where yet another pilot, Luis Carranza, flew him to Costa Rica.

Caro Quintero and his entourage, which included several cronies and his girlfriend Sara Cosio, passed through Customs unchecked upon arriving in San José. According to some reports, they may have first landed at an unsupervised provincial airstrip, making their arrival in San José a domestic flight exempt from passing through Customs.

The participation of so many CIA contractors in Caro Quintero’s escape raises questions about whether the CIA might not have arranged for Caro Quintero to come to Costa Rica, where he could be more readily nabbed.

“Absolutely not,” Berrellez said. “The only reason the Costa Rican government moved to arrest him was because we [the DEA] told them exactly where he was.”

The DEA had pinpointed the drug lord’s location by tapping a telephone at the Mexican home of Cosio’s parents. Cosio had called home and tipped off the DEA, Berrellez said.

In the early morning hours of April 4, 1985, Costa Rican cops, accompanied by DEA agents, stormed Finca California, a mansion in the Ojo de Agua area of Alajuela near Juan Santamaría International Airport, and arrested Caro Quintero and his cohorts.

According to press reports, Caro Quintero complained to the arresting officers that he had paid handsomely for refuge in Costa Rica.

Later that morning at the DEA’s office in the U.S. Embassy, DEA-agent-in-charge Don Clemens was on the telephone to Costa Rican officials trying to convince them to hold Caro Quintero for extradition to the United States, to no avail.

Instead, the Monge administration loaded Caro Quintero and his entourage onto an airplane and deported them to Mexico the same day the drug lord was captured.

Another Costa Rican Legislative Assembly commission, which investigated the circumstances surrounding Caro Quintero’s stay in Costa Rica, concluded that a “superior political authority” was responsible.

As for Caro Quintero, the drug kingpin vanished after his release last Julyfrom a Mexican prison. Mexican authorities ignored a U.S. extradition request.

In the ’80s, no one imagined the link between Caro Quintero’s ranch in Veracruz, Mexico, and the Santa Elena airstrip in Costa Rica – two pieces of a puzzle that on the surface had little do with each other.

While reporters have focused on isolated incidents, the entire picture of the Contra drug saga has yet to come into focus, according to Celerino Castillo, a former DEA agent and author of “Powderburns: Cocaine, Contras and the Drug War.”

“All this is very well documented, but no one has put the pieces together,” Castillo said. “But the pieces do fit together.”

Second in a series. Read the first part here.