In a print industry marked by downsizing because of the Internet, one small newspaper in Costa Rica seems to be hitting its stride, thanks to a largely untapped readership base and content that helps meet the needs of a large immigrant community.

La Nueva Prensa may only sell about 3,000 copies a month at ¢200 each, but its popularity is gaining among the Nicaraguan immigrant community in this country.

The Spanish-language monthly covers immigration and human rights issues, among other topics, and is increasingly becoming an informative bridge between Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

Founded in late 2007, La Nueva Prensa started as a four-page black-and-white newspaper with a monthly circulation of 500 copies. It was sponsored by small barbershops in San José and Nicaraguan sodas, the local version of small family-run restaurants. Today, it has grown to 16 color pages, and it has a website and social media networks including Facebook.

According to the National Statistics and Census Institute, 287,766 Nicaraguans reside in Costa Rica, about 75 percent of all foreigners living here, according to a 2011 census.

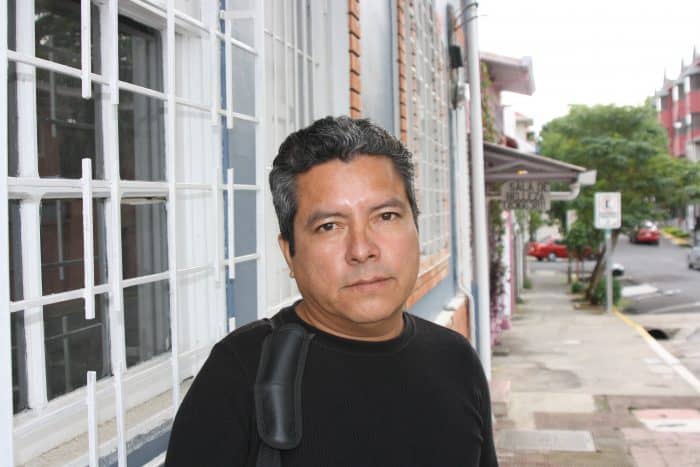

La Nueva Prensa was created to meet the needs of a community that traditionally doesn’t use social media networks, La Nueva Prensa Editor Alonso Mejía told The Tico Times.

Mejía, a correspondent for Nicaragua’s El Nuevo Diario, moved to Costa Rica from Managua eight years ago.

“Back then I worked in roofing. I came here like a lot of immigrants – to work in construction. I didn’t have immigration documents,” he said.

The idea to start a newspaper was his, along with journalist friend Julio Acuña, who died shortly after the business started.

“Along with Julio, I began to interact more with literary and journalism circles. When you have a passion, you try to make it work,” Mejía said. “I collaborated with publications, but they wouldn’t hire me because I didn’t have residency. That’s when we decided to start our own newspaper.”

The two didn’t have much money, but they “took a risk,” Mejía said. “We visited small Nicaraguan sodas to ask for support, and that’s how we started.”

Mejía took charge of the paper’s content, but he also had to learn to design, sell advertising and meet with clients.

‘Tico-Nica’ readership

La Nueva Prensa covers immigration, labor rights, cultural activities, the Nicaraguan economy and politics, and current events. Costa Rican writers collaborate on its cultural content.

“I think there is little information available here on the immigration issue, which is a fundamental topic in a country that receives so many immigrants,” Mejía said.

He noted that media in both countries often exploit immigrants in sensationalist news reports that foster “xenophobia, stereotypes and the negative perception that ‘Nicas’ are here to steal and rob.”

“But those reports are sporadic, and in reality there are thousands and thousands of Nicaraguans who are here, working for very low salaries,” he added.

Mejía describes La Nueva Prensa’s target readership on the Web – via a website and social media networks – as “Tico-Nica,” which refers to “the Nicaraguan who grew up here as a kid or who was born here to Nicaraguan parents, is in high school or university, and who uses Facebook.”

But La Nueva Prensa’s readers in the street, in a word, are “immigrants.” They often are older than 30 and include women who work as domestic employees and in sodas, and men who work as private security guards and as construction workers.

The paper’s readership is growing, and that has helped draw advertisers including Western Union and Importadora Monge, and telecom providers Móvistar, Claro and the Costa Rican Electricity Institute’s Kolbi.

Three employees sell the paper for ¢200 an issue ($0.37), and the company profits ¢100 per paper.

Readers can find La Nueva Prensa at bus stops in La Carpio, in San José’s Parque La Merced, and at the long lines outside of the Immigration Administration and the Nicaraguan Embassy. In La Carpio, papers also are delivered door-to-door. They’re also sold in Peñas Blancas, Costa Rica’s border town next to Nicaragua, as well as Alajuela and Cañas.

In the beginning, it was difficult to reach the paper’s target community, Mejía said, because many Nicaraguans who immigrate to Costa Rica come from a rural culture that doesn’t read a lot.

“It was tough at first because it was hard to reach people. But now, as we walk hand-in-hand [with our readers], it’s incredible how people seek us out,” Mejía said. “They look for our newspaper, they ask us when the next edition will be out, they call us from the ticket window at the bus stop in La Carpio. We’ve managed to reach people, and now a culture of reading La Nueva Prensa is developing.”